Mental Suggestions

The mind is everything. What you think, you become.

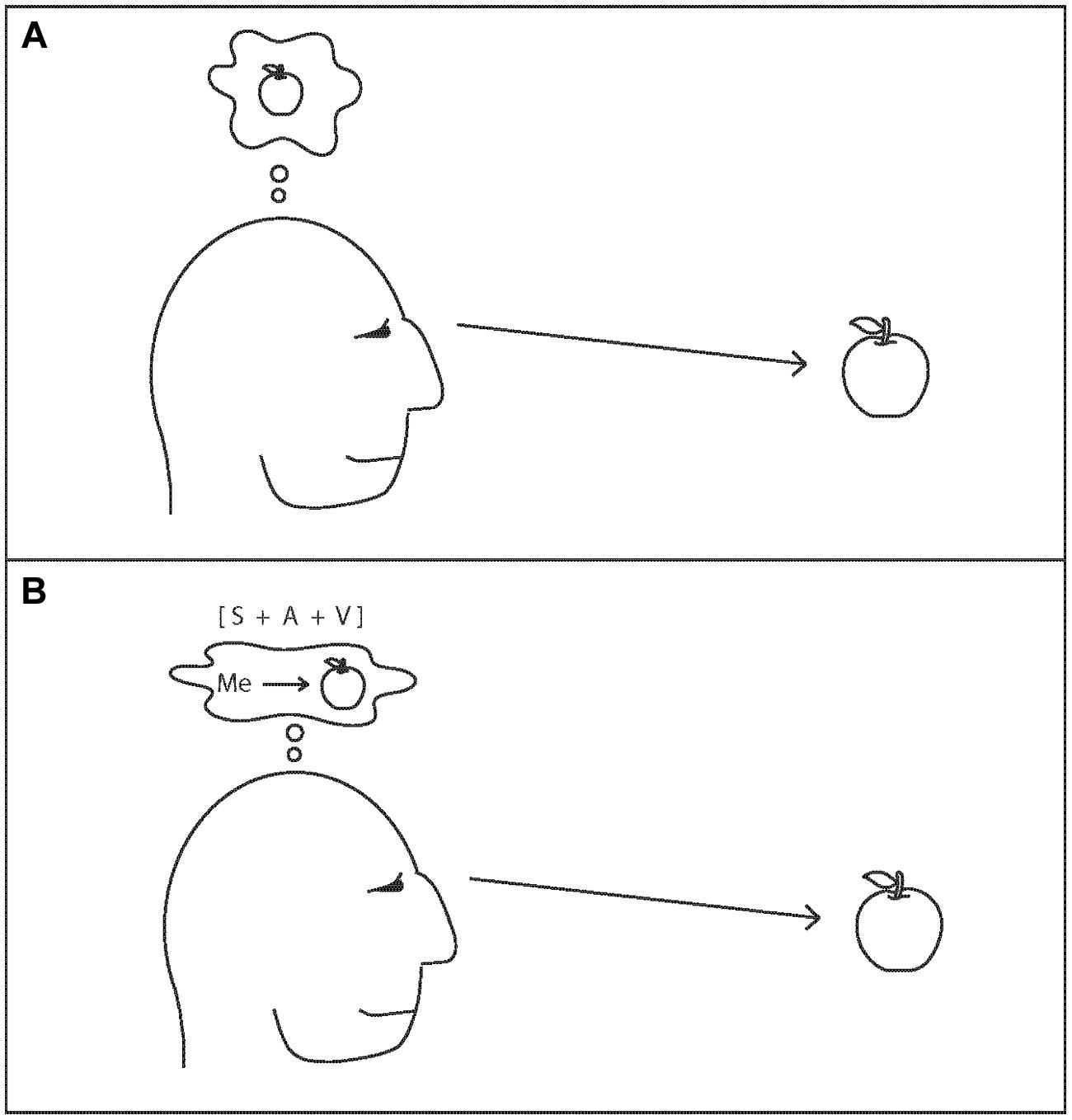

Mental perception is an integration of sensory perception, emotional perception, memory perception, and attention; everything that the person is aware of when making an appraisal of the environment and making decisions.

Despite that, the way that the mind does this integration is still not understood, and there are many competing models for how human conceptualization works — I’ve picked cognitive schema as the most broadly applicable here.

Schema

Everything we perceive about our environment and ourselves is categorized as concepts based on past experience. We have to, because the brain has no direct line to the raw physical world — it only deals with concepts. The brain resolves ambiguity and uncertainty by conceptualizing an internal model called a schema, and then uses that model to construct instances. Schemas are the lenses of the perceptual telescope: we need them to be able to perceive the world around us.

One important category of schemas are object schemas: the environment itself and the objects in it. For example, we have an idea of day time in a city, in an office building, and then the objects inside are categorized by function: a chair is something we sit on, a cup that we can drink coffee out of, etc. It’s so commonplace that we don’t realize that we even categorize these objects; we perceive these objects as already categorized into their appropriate schemas — we look at a large metal object with four wheel and automatically recognize it as a car.

Examples of schemas are beliefs, ideas, attitudes, stereotypes, social roles, and heuristics. Perception through schema is how the brain makes sense of the world. The use of schema to categorize and understand the world can even cause people to ignore or discard information that contradicts an existing schema, as it does not already fit inside the existing worldview. If it is out of mind, it is out of sight. When information contradicting schema cannot be ignored, people experience cognitive dissonance, and may change attitudes or beliefs.

Many hypnotic inductions contain the super suggestion to "make suggestions their complete reality" which calls for the hypnotee to change their perceptions according to the hypnotist’s suggestions. When it comes to the mind’s perceptions, this involves changing schema around their behavior, their environment, or themselves. Because schema are applied and processed as part of perception, the conscious experience is of dealing with the end result.

For example, one common hypnotic suggestion involves telling people that their hands have been swapped for feet and feet for hands. The hypnotee knows that they shouldn’t have feet at the ends of their arms. They may even remember being given the suggestion. But that doesn’t change the perception they have, because conscious experience comes after perception.

Because schema are applied in perception, they can quickly become part of automatic and unconscious processes. As the brain assimilates the schema, perception becomes more automatic.

Body Schema

Schemas are also how the brain keeps track of itself. The body schema is the internal model of the body, including the position of its limbs. The mind uses the senses to keep track of limbs, but can also be fooled with the rubber hand illusion, even to the point of body transfer and out of body experiences.

Attention Schema

Similar to the body schema, the attention schema keeps track of where the brain’s attention is going, providing the perception of awareness. The attention schema provides the brain with top down control to redirect attention and also allows the brain to understand the attention and awareness of others.

Awareness maps very closely to attention, but is not the same thing. Awareness is also not a full and complete picture of all the activity in the mind. Our awareness of our own mental state is a simplified and heavily sampled model, similar to how an emoji represents a human face.

Multiple experiments have shown it is possible to have attention without awareness, and even behavior without awareness, and the addition of an attention schema to AI models shows notable improvements.

Attention schema theory also has implications for dissociation, ADHD, and autism — I’m still looking for papers, but the concept of awareness as "perception of attention" is a compelling argument.

Agency Schema

The sense of agency is the perception of control over our own voluntary actions. It is divided into two levels: the immediate feeling of agency (which is closely linked with the body schema), and a higher level judgement of agency attached to background beliefs and contextual knowledge.

If it seems odd to think of agency as a schema, that’s because the agency schema is one of the first schema to develop in infancy. Very young babies have no clear sense of their environment or their control over their own actions, and must develop a sense of what they can control and differentiate between the environment and the self. Nevertheless, the sense of agency is a schema because it is actively constructed by the brain, and continually maps actions and events to cognitive executive decisions. It is both prospective and retrospective, incorporating both narrative and prediction.

Hypnotic suggestions often alter the sense of agency. People who are asked to perform a task outside of a hypnotic context may be happy to do it. If asked to perform the same action outside of a hypnotic context, the same action might be perceived as intentional. This may extend to full self deception, where the hypnotist is projected to be controlling actions directly.

This sense of control is so baked in that people at stage hypnosis shows will ask if the participants is "faking" the experience. This is not a question about whether they followed the suggestions — instead it’s a question whether the participants retained an internal sense of agency as they followed the suggestion. Sense of agency matters to onlookers in a profound and fundamental way — changing someone’s beliefs or emotions so that they willingly follow hypnotic suggestions is not nearly as impressive as "making" someone do something, even though automaticity can make unconscious actions seem conscious.

Self Schema

The idea of self is a set of schemas. There are many components to the sense of self ranging from the immediate sensory experience of self to the general philosophical and sociological concept of self: self-concept, self-esteem, self-identity, social self, and so-on. The term 'self schema' is usually used to denote beliefs about the self, for example "I work too hard" or "I’m very interested in hypnosis."

Identity formation is a crucial part of infant development. Hypnotic suggestions that alter the sense of self are very common place, ranging from ego strengthening exercises to believing they are the opposite sex.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and schema therapy has done a huge amount of work in covering self schema. You should not attempt therapy, but there are many useful tips and tricks available, and CBT plus hypnosis has been shown to be more effective than CBT alone.

Social Schemas

Other things in the environment are perceived in terms of social schemas: person, role, or event (aka script) schemas. There’s an assigned role that we are enacting (office worker), or there’s a specific event taking place (staff meeting), and we’re talking to a particular person that we have a relationship with (Phil the manager).

Through hypnotic suggestion, we can change the object or social schemas and change perception as a result. Given a known role (bride at a wedding), most people can seamlessly follow the script associated with it. This is a mainstay of stage and street hypnotists, who will suggest that the participants will see themselves as naked or be convinced that the hypnotist is their favorite celebrity.

Intention Schema

There’s a category of mental suggestion that doesn’t seem to directly involve schemas or perception at all: directing behavior. Some behavior is based on automaticity, as in Simon Says, but this does not explain post-hypnotic suggestions or more complex behavior that can come from simply saying "When I say X, you will do Y."

Behavior does involve perception in a subtle way though: it is a response to the perception of the future.

Breaking it down into pieces, behavior is a series of intentional actions. Intentional actions are anticipatory goal-directed movements based on predictions of the future: we see what could happen and what we want to happen, and move to make the desired future happen.

We may see several possible plans of actions, but we can only ever intend to perform one of them. The actions that we can decide on are the perceivable actions already filtered through schema — we don’t perceive the actions outside our schemas any more than a chess grandmaster would perceive an illegal chess move. Intentions are formed from schemas, and may be schemas themselves.

Hypnosis can alter the perception of future, the perception of the available options, or the perception of action. If the hypnotist suggests an action, the hypnotee may perceive is that it is the only action imaginable, or may have an expectation that the action will happen regardless of their intentions, or may perform the action while thinking they are doing something else.

Beginner Suggestions

Some useful beginning categories are agency suggestions, ideomotor suggestions, role suggestions, and activity suggestions. These give your partner interesting and new experiences without asking too much of them.

Ideomotor Suggestions

Ideomotor ("unconscious movement") suggestions involve movement of the body or inability (aka catalepsy) to move the body. These are suggestions to make the arm stiff, feel an arm get lighter and lift by itself, or have feet stick in place. Hypnotic suggestions affect perception, so technically suggestions can’t directly involve motor control: they are typically a combination of agency suggestions and belief suggestions.

If you tell someone that their arm is as hard as an iron bar and can’t bend, their belief is what stops their arm bending. You’ve told them to actively believe that their arm can’t bend. They may know that they can physically bend their arm, but they can’t bend their arm and maintain that belief.

Other common beginner ideomotor suggestions are to freeze, flop, or engage in repetitive activities such as clapping or windmilling the hands.

Marnathas has a useful tip to get started on ideomotor suggestions: when starting with a suggestion, begin with a single piece and then add to it. For example, you might start by freezing someone in place. After you’ve established a freeze suggestion, you can combine it with other suggestions to create puppets, jedi mind tricks, or freeze buttons. There can be various ways of building up complex suggestions and building versatility into simple suggestions.

Role Suggestions

Suggestions involving mental perceptions often involve playing a role. The best way to approach this is as a game with an open-ended premise that lets your partner involve their creative side. Similar to improv, these kinds of suggestions serve as a platform that enable new behavior.

For example, suggesting to your partner that they are a cat that can talk enables more behavior than suggesting that they cluck like a chicken, because there is more opportunity to express themselves. You can involve a laser pointer and have them chase it, and they can tell you exactly what they’re going to sit on and demand scritches.

Activity Suggestions

Activity suggestions will add or change the relationship of objects to the hypnotee, such as suggesting that an onion is an apple, or the aforementioned hands are feet suggestion.

Activity perceptions are often easier than sensory perceptions. Your partner may not be able to see a dinosaur in the room, but may be able to believe that there’s a dinosaur in the room if they are hiding from it. Likewise, convincing people that a shoe is a phone is a common trope in stage hypnosis, because the purpose of a phone isn’t what it looks like.

Thought Suggestions

Suggestions in altering thought patterns are as old as hypnosis itself. The classic is to tell your partner that they have no thoughts, but you can also add thoughts, redirect common thoughts, and have your partner do various mental exercises to train thoughts. Although you shouldn’t use CBT as therapy, there are a bunch of useful techniques in CBT that can be leveraged, such as this fish tank exercise.

This also applies to mental constructs like numbers. One common thought suggestion is to forget a number between one and ten. This is done by suggesting that the mind will skip over the number when counting, and not register it consciously if they see it.

Making Good Suggestions

The field of mental suggestions is too large to adequately cover completely. Instead, let’s focus on what what suggestions can do, and what good suggestions look like.

|

Following the same suggestions over and over again will lead to increased automaticity of those suggestions as they become procedural memory. This includes the habit of being hypnotized and following suggestions itself. If you have particular suggestions that you use, those suggestions will also get more automatic and eventually become conditioned responses. This includes habits of thought. If you repeatedly believe and act a certain way, those beliefs and actions will become habit, and become harder to disentangle from your own beliefs and actions, even if you think you are only pretending or doing it for show. Safety suggestions may help, but they may not be completely effective and you should not rely on them. The risk is that despite giving your partner safewords and talks about their own sense of agency and safety, it can become very easy for your partner to fall into a role or behavior unintentionally, and may find the role or behavior popping up in unsafe ways. This is a particular problem with personality play. |

Most of the time you’ll want to give suggestions that your partner will follow. What to do?

First, have an idea of the suggestion and the experience. Use the different kinds of perceptions as a guide.

-

Sensory: What do you want your partner to see, hear, smell, feel in their body?

-

Memory: What do you want your partner to remember or forget?

-

Emotion: What emotional reactions do you want your partner to feel?

-

Object Schema: What do you want your partner to believe about the world around them?

-

Body Schema: How do you want your partner to perceive their own body?

-

Attention schema: What do you want your partner to be aware of?

-

Agency schema: How in control do you want your partner to feel?

-

Self schema: How do you want your partner to think of themself?

-

Social schema: What social role or interaction do you want your partner to enact?

-

Intention schema: why does your partner think they are following the suggestion?

You don’t have to have an answer for all of these questions. When you have an idea of what you want them to experience, start thinking about what you need to do to bring them to that experience.

First, you should think about how and when to present the suggestion. Going back to the guidelines, your suggestion should first of all make sense.

-

Clear: Does your partner know what to do? Do they have a cue for when or where they’re suppposed to do it?

-

Context: Is your partner in a perceived environment or social role that makes this suggestion reasonable?

-

Congruence: Is the suggestion inline with your partner’s beliefs and values?

-

Coupled: Does the suggestion build on or follow on naturally from previous suggestions?

-

Closed: Is the suggestion timeboxed and limited so it applies safely?

In addition, your partner will have some traits of their own that influence whether they follow the suggestion.

-

Automaticity: Is this a behavior that your partner can do without thinking?

-

Motivation: Is your partner motivated to enact the behavior?

-

Engagement: Is your partner involved in the scene surrounding the suggestion?

-

Attachment: Does your partner have any attachment to beliefs or ideas that could hinder the suggestion?

Some suggestions, like arm-raise ideomotor suggestions, require very little setup. Other suggestions need more setup. Determining the amount of work needed for a suggestion to work for your partner is a skill, and like everything else it’s a skill that you will have to work at through trial and error. There is no "hypnosis scale" or "deep trance" that determines responsiveness to a particular suggestion.

You should tailor your induction so that it sets the scene and matches the suggestions that you want to give. If you want your partner to go for a run around the block, for example, you should set up with an alert induction.

Sales and marketing books can be great sources of inspiration when brainstorming suggestions. For example, Persuasive Patterns lists just about every possible factor in decision making and even suggests ways to combine patterns, although I think the website itself is far more valuable than the card deck they sell.

Automaticity

Most of our behaviors are automatic by default. If you suggest a behavior or role that is familiar to the point of being automatic, your partner is far more likely to follow it. This is true for even complex behaviors, like getting up in the morning and driving to work.

For example, if your partner is in the habit of running, you can suggest to your partner that they run around the block and they’ll do it without a second thought. To them, it’s like getting up from the couch or getting coffee.

Automatic doesn’t mean unconscious, so much as fluent. It helps to think about automaticity as the engine beneath actions. In the context of doing laundry, our conscious awareness is of "doing laundry" and not "picking this t-shirt and folding it." Generally, we do things because we’re supposed to do them. Once we’ve done the thing, we look up and look to the next activity. We don’t usually ask why we’re doing the thing once we’re involved in doing it.

Motivation

There are two parts to doing something: having the intention to do it, and having the motivation to do it. Motivation comes from a drive to satisfy inner wants and needs. Your partner may have the intention to go for a run, but if there’s no motivation and they have not run enough to make it automatic, they may find it hard to get started.

Desire

Desire is the easiest path. Your partner should want to do the thing, to the point where not doing the thing is unbearable. If your partner really wants to go for a run, then not running is the worst torture imaginable. You can suggest the imagery of running, remind them of how much they enjoy the feeling, and how much they need to shift and move their legs. Have your partner feel their current level of enthusiasm, then imagine what it would feel like to be more enthusiastic, then have that feeling inhabit them.

If there’s no intrinsic desire to run, you can create an extrinsic desire. You can hold out a reward for the end of the run, or a larger reward that the run will add progress to. For some people, it might be an explicit reward system, i.e. pleasure, headpets, or praise. For others, it might be accomplishment or the satisfaction of routine. You should be able to find something that they want and link it to the suggestion.

Rewards that are unlocked by successful completion of the task can be particularly useful. For example, your partner can buy food for pickup at a place near the midpoint of your partner’s run, or your partner can listen to a favorite podcast only when running, a practice known as temptation bundling.

If your partner is following a suggestion that alters their role or their sense of self, you should think about what the character want. If your partner is being a cat, their motivation is to get headpets and scritches or the demand to be fed. If your partner is being a superspy, their motivation is to seduce their contact over dinner.

|

It’s generally a bad idea to use fears or insecurities as motivation, as you don’t always know how emotionally intense it can get or how real it can seem. The idea of beating the blerch might sound good in your head, but your partner probably doesn’t want to be literally chased by their demons. |

Baby Steps

If your partner is not highly motivated, you can still make use of your partner’s low motivation by using micro suggestions, also known as baby steps.

Motivation can build up over time from completing smaller related activities in service of the larger goal. By breaking down one large suggestion into several smaller suggestions, you can build fixation and readiness for the task.

For example, if your partner is lukewarm at best on running, then rather than telling them to run and pushing them out the door immediately, you get them on the path to running by focusing on small goals, optionally with small rewards attached.

-

Suggest they change into running clothes. Reward.

-

Suggest they stretch. Reward.

-

Suggest they do warm up exercises. Reward.

-

Suggest they walk to the end of the block and back. Reward.

-

Suggest they can only walk to the end of the block, and can finally run when they turn the corner.

Often its the initial inertia has to be overcome, and then the response to suggestions will snowball. Make sure you keep pace with how they are responding; you may need to shift to larger suggestions as their responsiveness builds over time.

This is one point where using a permissive double bind can be useful, e.g. you can ask them if they want to wear shorts or sweatpants for running clothes.

Engagement

Engagement and motivation are closely related, but motivation is a commitment to a goal. Engagement is a commitment to the bit. If you want your partner to go for a run, put them in a scene where running is not the end goal, but a natural part of the bit.

Narrative

Engagement is an exercise in storytelling narrative where your partner is the protagonist. You set up a scene, then use that as the base reality that you engage with from different angles using different situations. Depending on your partner’s involvement, it can range from improv to roleplay to actual immersion. Again, work on engagement by building up responses a bit at a time, building on already followed suggestions.

Engagement can be about the environment around your partner, but it can also be about your partner’s self image. For example, you can have your partner believe that they are at school by having them interact with the whiteboard, make faces at the teacher while their back is turned, or write love notes to their crush. You can have your partner believe that they are a robot by having them feel their movements be robotic, then have them become slightly buggy and (safely) misinterpret commands.

Using narrative also adds narrative tension and the drive to fulfill narrative tropes. Narrative tropes need not be explicitly stated: if your partner is a Doctor Who fan, setting a scene with you as the Master and your partner as the Doctor’s so very alone female companion carries a certain implication.

Going back to the running example, you can exploit narrative for your own goals. In romance, there’s a meet-cute, then the tension of flirting, then a dramatic run through the streets at the very end to meet again and declare devotion. You can put your partner in that scene and have them run around the block to meet you and sweep you up in their arms.

TVTropes can be a surprisingly good source of material, including summaries of just about every activity you can think of, i.e. looking for running material will take you to the ZombiesRun page. Creating a scene also has a lot in common with improv: Impro for Storytellers is a great starting point for how to project and act in the moment.

Trouble

Part of the reason that stories and narrative are so effective is that human brains are wired for trouble and signs of trouble.

You can exploit this to build tension and release. You can introduce time threats (this opportunity will be gone in 10 seconds!), resource threats (this is the very last cookie!), or environmental threats (the floor is lava!).

Going back to the running suggestion, if you know your partner has a competitive streak, you can build engagement by providing some competition, real or imagined. The tighter the race and the less certain that your partner is going to win, then more tension your partner is going to feel and the greater the release when they finally win.

Attachment

I’m using the word attachment here in a roughly Buddhist sense here to talk about prior beliefs and preconceptions that your partner may have that gets in the way of following your suggestion.

Maladaptive Schema

The first kind of attachment is a deeply held maladaptive schema that has an emotional impact. This is the most serious kind of attachment, and your partner might be completely unaware that they have this belief up until the point that it applies. For example, your partner may feel that they look ridiculous running in public, and that people will laugh at them. At that point where they get closer and closer to the door, your partner may stall or freeze up and look extremely unhappy.

At this point, STOP. Take care of your partner first and make sure they’re okay.

Sit down, talk about it. Don’t try to change their mind or hypnotically convince them that they look fine. If your partner suggests a course of action and wants to push through it, then follow their lead and support them as they work through it. If not, then drop any lingering suggestions and either move on to something else or call an end to the session.

Reframing

Other attachments may not have emotional impact, but may be just in the way. For example, mathematicians can get hung up on forgetting a number when counting to ten, since they have a very strong of numbers in general. In this circumstance, you can remove the attachment by reframing the issue, e.g. telling them that this is a kind of number system and because their brains are so good at numbers they can find they can count and think completely naturally in base 10 sans 5.

Challenge

If your partner has an attachment to a belief that needs to go and you don’t want to reframe the suggestion, you can challenge the belief. This will shake their belief up and cause them to reassess and reevaluate. Weakening the belief directly can cause confusion, creating uncertainty and ambiguity. As with physical perceptions, uncertainty in perception opens the door to suggestion and asserting a new belief.

You can pose the challenge in different ways. You can ask them to suspend or ignore the belief, and accept a new belief wholesale for the duration of the session. Or you can ask them to remove the belief, placing them back in a position of uncertainty, and then walk them through the new belief.

This is best done with uncontroversial and simple topics that your partner does not have strong opinions on. Your partner may not care if you tell them to believe that nuns are made in factories or that the Sun revolves around the Earth. They will absolutely care if you tell them to believe that season 8 was the best season of Game of Thrones.