Components of Hypnosis

You are not expected to understand this.

We can look at the common components of a successful hypnosis session and the research efforts to maximize suggestibility.

Pulling in the definitions of Context and Suggestibility from the previous section, we can include the following useful components:

-

Context: a social expectation to assume the roles of hypnotist and hypnotee and give or follow suggestions, respectively.

-

Rapport: the connection between participants.

-

Expectancy: the expectation (conscious or unconscious) of an experience.

-

Imagination: the creation and enactment of suggestions.

-

Suggestibility: the quality of being inclined to accept and act on suggestions.

There are variations in the ways that these components are conceptualized, but this list has remained relatively constant since at least the 1970s. There are other conceptions: Wordweaver initially conceived of these factors as CREAM, Delusioness has SEAM, and Daniel Araoz introduced the acronym TEAM in the 1970s.

It may help to imagine hypnotism as a function: in a hypnotic context C, maximizing the input components will maximize effective suggestibility.

C(REI) → C(S)

Technically, it doesn’t matter how these components converge, and they do not require a formal induction to be present. Inductions are the norm because people expect them as part of hypnotism, they do increase response to imaginative suggestions, and they play an important role in establishing hypnotic context.

Let’s describe each component in detail and decompose them using academic theories to put together an idea of how hypnosis could work.

Context

The first step is establishing a hypnotic context; a situation in which the participants understand that hypnosis is going to take place.

Context is very important because it replaces the usual social conventions and establishes the ritual and the roles of hypnosis. For example, in a hypnotic context it’s appropriate and expected to have people close their eyes and follow suggestions that their eyelids are stuck together, something that doesn’t happen in normal conversation. Establishing a context may involve a formal induction, or it may be as simple as saying "we’re starting now, say when you’re ready."

Negotiation, pre-talk, and setting are all part of establishing a hypnotic context. Setting the scene establishes the roles of hypnotist and hypnotee, priming the hypnotee to conceptualize any change in perception and experience as being hypnotized.

Rapport

Rapport is the social and emotional connection that comes from empathy and established trust. Rapport starts with co-regulation of the nervous system, noting the tone, speed, and animation of the other and matching it. This process is called pacing, mirroring, or matching. In clinical hypnosis, the hypnotist matches the energy of the hypnotee. In stage hypnosis, hypnotees are expected to match the energy of the hypnotist. In recreational hypnosis, it’s typically a joint effort.

The process of building rapport begins well before a hypnotic context is established, as it’s about building a personal connection first and foremost. This means that negotiation, pre-talk, and setting expectations are all a part of rapport. Rapport has been shown to improve motivation and attune attention.

In particular, Mr Rogers was a master of building rapport. Here’s a video of Mr Rogers along with a breakdown of how he speaks and relates to a hostile senator.

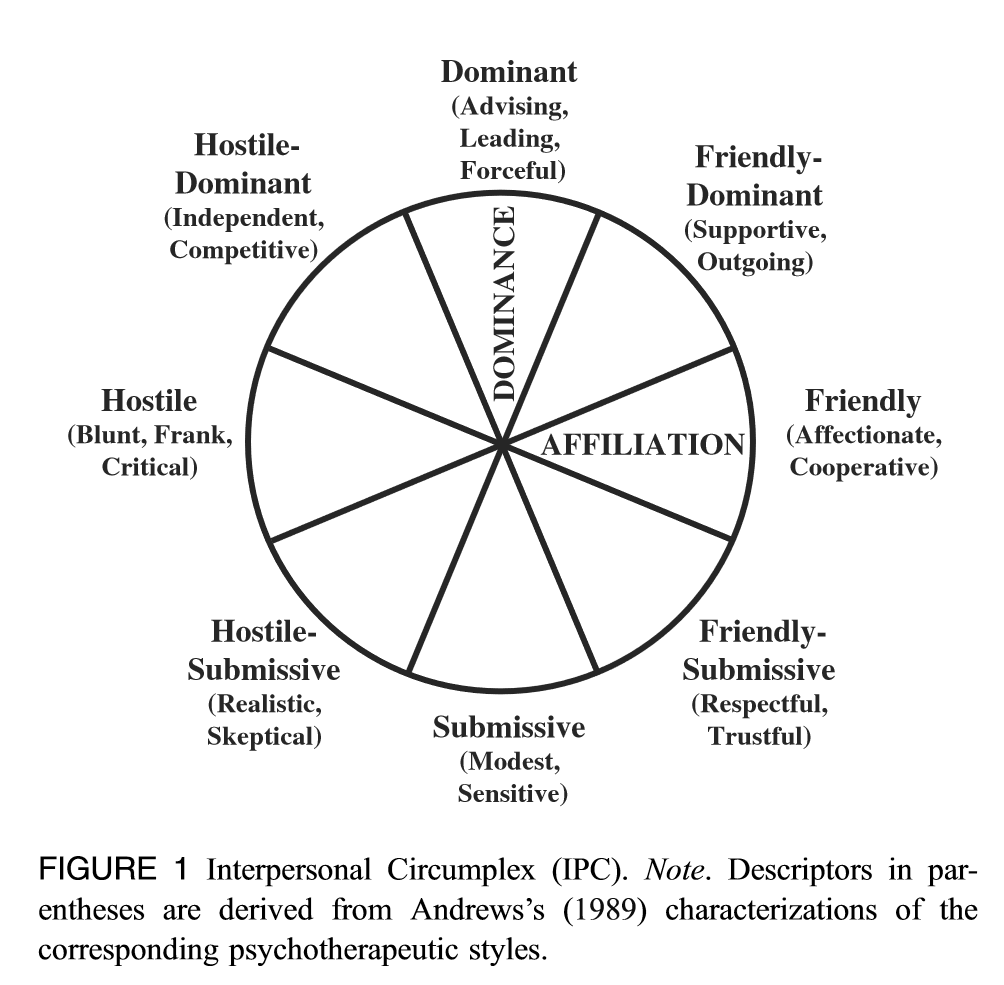

The ability to adapt to interpersonal style is a key piece of rapport. Styles can range wildly between hypnotists, from authoritative and aggressive to agreeable and submissive.

Rapport is also built through convincers and suggestibility tests, where the hypnotee follows an instruction and gets positive feedback when completing it. The hypnotee can also vary in their response, from amnesia-prone, dissociaters, inward attention, or the relaxation types… or even a mix of all of them. Different inductions and suggestions are appropriate for different people. Some people want to feel controlled, and some strongly dislike the "puppeting" implied in suggestions. Some may find suggestions that multiply depth by a number i.e. "ten times as deep" to be mathematically impossible.

Rapport includes the ability to read and respond appropriately when someone is comfortable or uncomfortable, and how they express themselves non-verbally. Non-verbal communication, such as tics or shifts in the body, can reflect tension when hearing a suggestion. Rapport is built through many small interactions showing that the hypnotist is watching and listening to the hypnotee, and it can be as subtle as rephrasing a statement as a question in response to a frown. Rapport is also involved in pausing the session and seeing when the hypnotee may need a break — when you read about hours long sessions, they typically include regular check-ins and breaks, followed by reinduction.

Expectancy

Response expectancy theory (1985) describes the brain as an anticipation machine wired to respond rapidly to the environment, using perceptual templates or expectancy to resolve ambiguities very quickly, and asserted response expectancies could generate the hypnotee’s experiences. This paper was a big hit, as it provided an underlying mechanism for both hypnosis and placebos and a mechanism for automaticity.

In psychology, an expectancy is a belief by the brain that something will happen in the future. There are two broad categories: stimulus expectancies and response expectancies. Stimulus expectancies are beliefs about the external world will act (seeing a colored shape along with an electric shock), and response expectancies are beliefs about the organism will react with a nonvolitional (emotional reactions, pain, tickling) response to the external world. Classical conditioning is included as a component in the response expectancy model, but the assumption is that classical conditioning takes a very small role in organisms capable of complex cognition.

At the time, it was not known how expectancies manifested in the body (the mind/body identity assumption) and although some links were obvious (particularly in fear based expectancies) it was not clear how expectancies could change emotions or thinking.

Response Set Theory

Response set theory (1997) builds on response expectancy theory to add automaticity by talking about behavior in terms of automatic sets of responses that we only think we have control over. The very short version is that conscious thought is the very last step in the chain of processing; by the time we decide to do things, the brain has already decided to do it for us. A follow up paper, The Response Set Theory of Hypnosis (2000), cleared up some misconceptions on the earlier paper, but still held that actions are fully automatic.

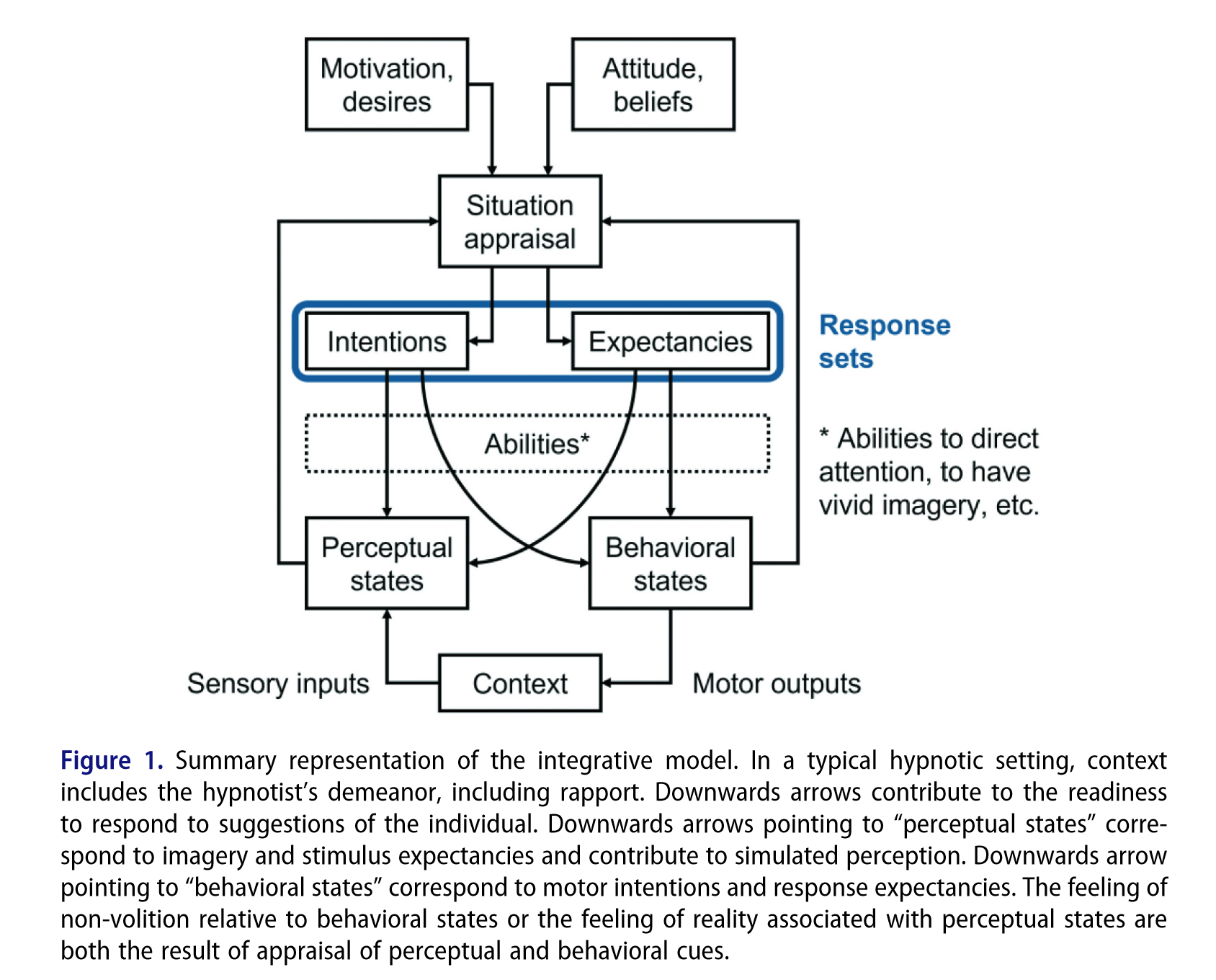

Integrative response set theory (2022) steps back from fully automatic actions, instead saying that varying degress of automaticity precede actions, and uses a "weak" model of response expectancy that reflects more recent studies. The integrative theory provides a practical mechanism for response expectancies by integrating the model with the hierarchical predictive processing model in cognitive neuroscience, stating "an expectancy is by definition a prediction."

Response sets are vital in everyday habits and in complex decision-making like driving, sports, or computer games, where there simply isn’t time to make a conscious decision. Response sets themselves have been in use for a while; Erickson in particular was fond of yes sets for cuing behavior and implicit knowledge and deautomatizing maladaptive response sets.

Importantly, response sets can be either be conscious intentions or unconscious expectancy. The conscious attribution of agency differs, but the underlying automaticity is the same.

Here’s a great talk going into the details of response set theory starting at 41:26 (it is in French, so you will want to turn on auto-translate).

How can you have a response set in response to a suggestion that has never been given before? This is explained through the idea of a response set consisting of a generalized response expectancy or implementation intention: a motivated commitment to respond. At a high level, the hypnotee decides that they will follow suggestions, and committing to that intention creates a prediction about future actions. Once an intention is activated, it alters perception to put the steps to complete the intention at the front of the brain while sidelining irrelevant information.

You don’t need conscious awareness of the instruction or the cue. As long as there’s clear instruction and no further decision making is required, then complex goals-directed actions can be triggered directly by situational cues. If following instructions is the goal, then following instructions feels automatic.

Automaticity is subtle because the degree of automaticity only becomes apparent during response inhibition, leading people to believe that they are following the suggestion "of their own free will" until they try resisting suggestions. This behavior can be seen in a game of Simon Says, where the response set to immediately respond to the leader giving the instruction is given repeatedly. At some point, the leader gives an instruction without saying "Simon Says" and everyone has to inhibit their response to following the instruction. In just a few minutes, following the response set feels completely natural, and inhibiting that response is jarring.

This means that there are at least three different processes at work for the hypnotee:

-

Trance, the subjective experience of being hypnotized.

-

Intention in the decision to follow suggestions, and that intention may fade from consciousness.

-

Automaticity through a response set which can be experienced either as intentional (with a sense of agency) or involuntary (without a sense of agency), and may or may not be connected to the sensation of trance.

Richard Feynman has an anecdote showing how response sets can feel intentional while following a suggestion.

When the real demonstration came he had us walk on stage, and he hypnotized us in front of the whole Princeton Graduate College. This time the effect was stronger; I guess I had learned how to become hypnotized. The hypnotist made various demonstrations, having me do things that I couldn’t normally do, and at the end he said that after I came out of hypnosis, instead of returning to my seat directly, which was the natural way to go, I would walk all the way around the room and go to my seat from the back.

All through the demonstration I was vaguely aware of what was going on, and cooperating with the things the hypnotist said, but this time I decided, "Damn it, enough is enough! I’m gonna go straight to my seat."

When it was time to get up and go off the stage, I started to walk straight to my seat. But then an annoying feeling came over me: I felt so uncomfortable that I couldn’t continue. I walked all the way around the hall.

Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!

This example also suggests how involuntariness arises, in that either the suggestion is resisted or the suggestion itself places agency outside of self by suggesting that something is happening to the hypnotee.

Predictive Processing

At this point, the big question is how response set theory matches to how the brain works, and why this is a better model than the "hidden observer" theories popular in hypnosis books from the 1970s. The answer is that there is no subconscious mind, only unconscious processing.

[A]ccording to modern neuroscience, the brain is not organized hierarchically such that stimuli move “up” to increasingly complex analyses until they reach some high level that makes sense of it all. Rather, there are many operations occurring simultaneously, in parallel, and our belief in the unity of experience is illusory. Hypnosis and other special circumstances reveal this. They are simply demonstrations of how the mind/brain operates normatively and not some special mind/brain state. The views of Janet, which have come down to us in more sophisticated form in Hilgard’s and subsequent work that maintained the idea of some split, are simply not correct. The second mind of Puységur, instantiated as a hidden observer, is also not reflective of how the mind/brain operates. These views do not reflect the way neuroscientists think about the mind/brain anymore. They are anachronisms.

…

We think [response set theory] can be enriched by a deeper connection to current cognitive science models of cognitive architecture: massive modularity, connectionism in the form of PDP, and neural reuse. Massive modularity allows for the possibility of an unconscious module that truly makes consciousness illusory (i.e., the interpreter and/or the SCI). PDP and neural reuse deny the existence of higher and lower centers. All require parallel functioning in the mind/brain and therefore deny the unity of experience. Thus, there is no need for a concept of dissociation because there was no preexisting unity. All three models also aver that everything in the mind/brain is constructed and largely unconscious. It is consciousness that is the mystery, not behavior that seems to lack consciousness.

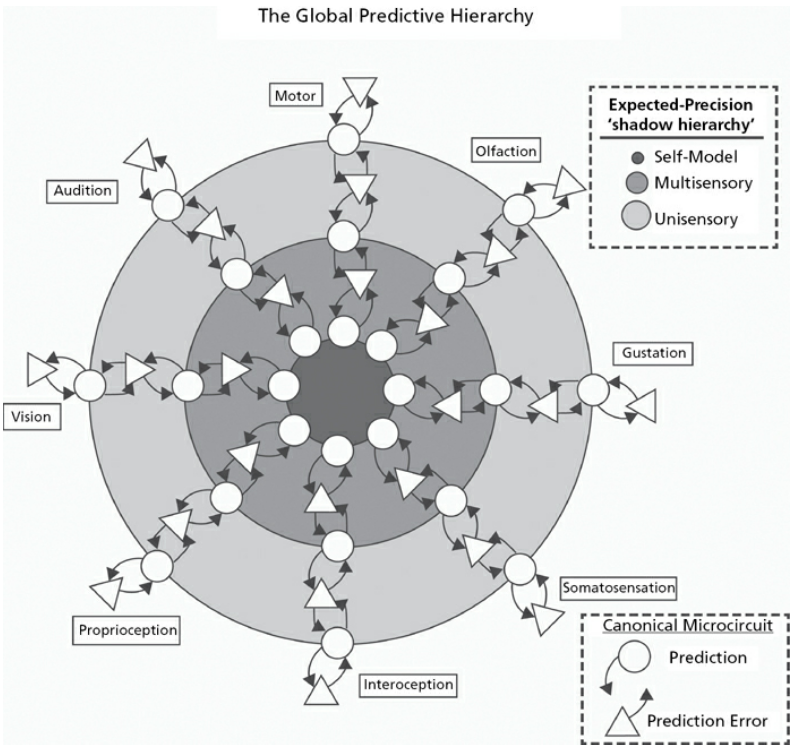

The question is how that processing turns thought into action. Predictive processing theory (2020) provides an idea of how expectancies and higher level response sets turn into low level actions and nonvolitional responses. It describes cognitive processes as a set of internal models that are continually tested and updated by underlying models, eventually taking input from sensory channels. If a model conflicts with the underlying input, it’s described as a "prediction error" and sent upstream until the error is corrected.

This youtube video gives a good overview of predictive processing:

From The Interoceptive Mind From Homeostasis to Awareness there is this diagram showing how the core models integrate information that has already been filtered and processed through many layers of predictive processing:

The core models do not ever interact with raw data, but only deal with lower level models which propagate their errors upstream.

This provides a neat explanation of how hypnosis can change perception, because all perception is built by comparing sensory input against an predicted internal model and noting prediction errors.

But predictive processing applies to more than just sensory input. Going back to emotion suggestions and mental suggestions, both emotions and cognitive schema can be viewed as established models (technically predictions called "bayesian priors").Predictive processing is also an explanation of agency and decision making, because beliefs and desires are essentially free-standing predictions.

Desires, intentions, and motivations are now all realized as varying forms and time-scales of prediction. Desires thus realized are standing (generative model-based) predictions that become active and positioned to entrain actions according to the context-varying flux of precision weighting.

[A] major role of prediction (in PP) is to bring about the statistical patterns in behavior that define us both as individuals and as a species. Relatedly, the estimated precision of specific predictions is not, as is sometimes thought, simply a measure of systemic confidence in their accuracy or reliability — rather, it is a device that actively positions some predictions for the control of behavior.

Interoception and Allostasis

Predictive processing can provide the neural correlates for response expectancy, but it does not provide a model of how the brain can cause nonvolitional changes in the body and account for the "mind/body identity assumption" in response expectancy theory.

Similar to the way that the brain perceives its environment, the brain also senses its own internal state through interoception and maintains an internal model of the body. The interoception and imagination loop in hypnotic phenomena (2019) provides a starting point for viewing hypnotic phenomena through interoception.

The brain takes note of differences between its internal state and its anticipated internal state, and resolves the difference through allostasis as a control feedback loop. Crucially, allostasis is a predictive homeostasis — it allows the body to proactively prepare for events before they happen and react accordingly.

This potentially closes the loop on how the brain affects the body through hypnosis. Allostasis as control mechanism very neatly explains hypnotic phenomena that don’t fit into environment-based nonvolitional responses, like wart removal. (I am extrapolating here — as far as I know, there are no papers directly linking hypnotic phenomena with allostasis, but there is some research showing evidence of an intrinsic allostatic–interoceptive system in the brain.)

Dr Lisa Feldman Barrett discusses allostasis and interoception in this youtube video:

Because internal responses in the body can be ambiguous and interpreted in many different ways, expectancies about responses are self-confirming: we may feel the way we anticipate feeling, including how we feel emotions and motivation, and our perception of self. Emotions in particular are described as cognitively created conscious experiences, with arousal and interoception as non-emotional ingredients. This is an area of active research, and some papers are downright fascinating, for example describing fatigue and depression as a self-belief (read: response expectancy) in the body’s inability to self-regulate effectively.

This also provides some hints into how strong beliefs about hypnosis efficiency can cause more effective outcomes; a response expectancy that hypnosis can cause allostatic hypercompetance could be self-fulfilling. Likewise, a sense of involuntary action could be described as interoceptive prediction error, where the sense of self does not account for hypnotic suggestion.

Imagination

Imagination is both self-explanatory and somewhat confusing. Given that hypnosis is supposed to involve automatic or involuntary behavior (aka "classic suggestion effect"), how does imagination make any difference?

There’s overlap between imagination and perception. Those lines can be blurred, or can even move.

It comes back to the generalized implementation intention. In the same way that a game of Simon Says is much less fun with someone who doesn’t want to play, hypnosis needs active co-operation and involvement on the part of the hypnotee. Unfortunately, hypnosis is typically not seen as a game played between hypnotist and hypnotee, but as something the hypnotist does to the hypnotee, leading to passive behavior.

In fact, a large portion of hypnotic suggestibility comes down to the mindset, motivation, creativity, and experience of the hypnotee.

Motivation

Hypnosis, Suggestion, and Suggestibility: An Integrative Model (2015) walks through the steps in a hypnosis session and describes various contributing factors (much like this page does) that go into it, including a description of response sets. In particular, the paper points out that the best results are achived with those "motivated by curiosity, the wish to achieve an altered state of consciousness, and succeed at the task at hand."

In recreational hypnosis, motivation is something that improves naturally with every positive session. It’s common for people who are lukewarm or even slightly negative on hypnosis to become highly motivated as they find what works for them and what they really enjoy in the experience.

Carleton Skill Training Program

An educational training procedure called the Carleton Skill Training Program (CSTP) was developed to model effective hypnotic behavior and has shown good results. The original CSTP is over an hour long, but a four minute version is just as effective, and is reproduced here.

The last time you were here you scored as low in hypnotic susceptibility. In today’s session, you will be given the same susceptibility test as you were before. However your task today is totally different from last time. I will give you instructions that will easily enable you to increase your level of hypnotic susceptibility substantially.

A common misconception about hypnosis must be cleared up from the outset. Hypnosis cannot change your actions and thoughts. If you just sit and wait for suggested responses to happen on their own, nothing will happen. If I suggest that your arm is rising, the arm will certainly not rise by itself. Likewise, if I suggest that you are forgetting something, this cannot make you forget in the least! With this in mind, pay attention to the two instructions that follow. If you do your best to follow both instructions, you will be able to increase your susceptibility level greatly.

First, make the suggested response happen automatically. This simply means that you should make each of the responses that are suggested, but don’t pay attention to the fact that you are making them. Automatic responses of this sort are commonly made in everyday life. For instance, when you are reading the newspaper, you might reach automatically for a cup of coffee and have a sip. Reaching for a coffee cup is something that you do with minimal attention because most of your attention is directed elsewhere to more interesting things (e.g. towards reading the newspaper).

Thus if a suggestion tells you to raise your arm, then lift your arm automatically; if a suggestion says that your arm can’t bend, then automatically make the arm so stiff that it cannot bend; if a suggestion says you can see a butterfly, then automatically let some sort of image of a butterfly appear; if a suggestion says you cannot remember something, then automatically push the memories out of your mind. The last time you were here, you may not have realized that you were to make the responses. It is no wonder, then, that nothing happened in response to the suggestions!

Second, devote all your attention to the suggestions. Suggestions can be thought of as little stories. Think of each suggestion as a little story that describes events that are happening to you. Your task is to concentrate as deeply as possible on the stories. Your very deep and continuous attention to the stories is what enables you to achieve hypnotic experiences.

To summarize: Make the responses that are suggested, but pay no attention to the fact that you are making them. Instead, devote your full, undivided, and continuous attention to the stories.

Automatic Imagination Model

The CSTP does a good job of describing imagination, but the language is a bit stiff. Another way of phrasing the same idea is the automatic imagination model, which asks the hypnotee to follow the suggestion intentionally, then imagine that the suggestion is automatic.

The insight that Ant and I had […] was that if everyday imagination can create reality, other than the fact we know that we’re imagining it, then we should be able to use the same mechanism (imagination) to create a reality in which we were unaware that we were imagining! In other words, use imagination to create the effect and then use imagination again to cover up the fact that we know that we’re imagining the effect. This should result in us experiencing the effect as if it is real, while being unaware that we are imagining it, hence being unable to stop it, and experiencing the effect as occurring automatically.

This can be tricky to convey, so I’ll try again. If we imagine that our hand is stuck to the table, then while we continue to imagine that, we will be unable to lift our hand; we will know that we’re imagining it, however, and can stop imagining it any time we want, in the blink of an eye, simply by needing our hand for something else. While we continue to imagine that it is stuck, though, it should remain stuck (based on the ideomotor hypothesis). If, while we’re imagining that it is stuck, we also imagine that we are unaware of imagining that it is stuck, as if it has happened all by itself, then we should experience the stuck hand without knowing how it happened, and therefore no way of undoing it.

The format of these sessions resembled a normal conversation where the hypnotist simply asked a series of questions and gave clear instructions, and the subject remained awake and fully alert throughout. "Can you imagine that your hand is stuck to the table?" - "Can you continue to imagine that and also imagine that you’re not aware that you’re imagining that, like it’s happening by itself?"

Here’s a Youtube video showing a demonstration of the automatic imagination model:

The automatic imagination model does pose some interesting questions. Normally, we would expect an explicit ask to "not think about something" to result in more thinking about something, as in the classic "don’t think of a pink elephant" problem. There is something about paying attention or attributing automaticity which does not work the same way as direct visualization thoughts — it could be working because it’s a perception task rather than a conceptualization task here.

Self Deception

One of the concepts that both the CSTP and the automatic imagination model recommend is to evoke the feeling of automaticity and involuntariness while making the responses, and then internalize that feeling.

This goes beyond response expectancy and ties into a theory of hypnosis as self deception, where deliberately role-playing and thinking of a response as involuntary can make subsequent responses feel more involuntary. This is a fascinating paper that has elements of suspension of disbelief, followed by resolution of cognitive dissonance that crosses over into self-gaslighting.

Along the same lines, adding implementation instructions of the form "I will suppress any thoughts about my intended behavior while performing the tasks!" and then adding the if-then plan "And if I receive a new task, then I will tell myself: Suppress now any thoughts about my intended behavior!" also provides an increase in hypnotic responsiveness.

Practice

As implied by the CSTP and the automatic imagination model, hypnosis is not a stable trait; in other words, hypnosis is a skill that can be improved with practice.

Academic papers tend to focus on many participants rather than building the skills of a few. Likewise, hypnosis is typically treated in books as an introduction for hypnotees, and does not focus on skill-building. The exception is Mind Games, which consists of hypnosis exercises broken up into four sections of increasing difficulty.

Recreational hypnosis has several instances of people who have improved their ability over the years through consistent practice and feedback. In particular, sleepingirl has written extensively on becoming a skilled subject along with specific exercises for exploring spontaneity, getting comfortable with thoughts, and understanding process.

Readiness Response Set

Hypnosis, Hypnotic Phenomena, and Hypnotic Responsiveness: Clinical and Research Foundations — A 40-Year Perspective (2019) describes a "readiness to respond" ability factor which seems to characterize some common behaviors in highly hypnotizable individuals. Integrative response set theory (2022) discusses the readiness response set in more detail — An Empirically-Informed Integrative Theory of Hypnosis (2024) also digs even deeper into this but is not covered here.

The paper breaks down into three main areas: singlemindedness, cognitive flexibilty, and a focus on attainable goals. Some of this may be strategy based, and some may be hard-wired abilities. Some combination of neurological differences may have an impact on readiness, as brain correlates have been found in highly hypnotizable individuals, such as differences in central executive network (CEN) and default network (DN) processing.

Singlemindedness

The paper lists four factors that together can be classified as "singlemindedness of thought."

Individuals who enact an RRS are relatively nonreactive to experiences such as distracting thoughts, sensations, and emotions that undermine stubborn predictions/expectations regarding their responsiveness to suggestions.

Instead, such individuals:

(a) focus on sensations and suggested events; (b) attribute their responsiveness to hypnosis or the hypnotist while they do not analyze, critically observe, or devalue their performance; (c) suppress, tune out, or “background” experiences that generate prediction uncertainty; and (d) tend to not engage in introspection or experience metacognitive awareness.

When they become distracted, such participants possess sufficient cognitive flexibility to fluidly redeploy attention to suggestion-related events and control their internal experiences and resources.

Cognitive Flexibility

In addition, somehow these individuals are very good at translating imaginings into "felt sensations."

The combination of the abilities we enumerated likely interact to generate stubborn predictions, aided by a little-studied ability to translate imaginings into “felt sensations,” which might increase the compelling nature of suggested experiences and solidify positive response expectancies.

Attainable Goals

Finally, highly hypnotizable individuals tend to set attainable goals to meet the suggestion using whatever skills and creativity they have.

However, successful hypnotic responses might not vary so much primarily as a function of different suggestion-related abilities but rather in terms of whether participants deconstruct suggestions such that they discern their requirements for responding successfully and, crucially, possess the requisite motivation to implement them. For example, Wallace (1990) found that low-responsive individuals may have the capacity to imagine suggested events but fail to do so because they do not choose to use imagery. To pass a so-called challenge suggestion to try to bend an arm stiff like a bar of iron requires that the participant develops an interpretation/strategy (Galea, Woody, Szechtman, & Pierrynowski, 2010) such as “If I really focus on the suggestion-related sensations of stiffness and not expend much counterforce to bend the arm, then I will pass the suggestion.”

Some of the techniques can be seen in this case comparison that gives helpful examples of intentional belief, saying "in order to block out the third box, you just tell yourself that you don’t see it."

Suggestibility

Finally, the end result is suggestibility. But what is suggestibility?

What is Suggestibility?

Unfortunately, asking this question is tantamount to asking what hypnosis really is, with the same problems. Wikipedia has a subsection saying "Hypnotic suggestibility is a trait-like, individual difference variable reflecting the general tendency to respond to hypnosis and hypnotic suggestions." Specifically, suggestibility is an indication on an experimental scale of how many suggestions the hypnotee can follow, ranging from lifting an arm to amnesia and hallucination.

There’s been criticism about the methodology of suggestibility scales, and more recent studies prefer component models of suggestibility showing differences in responsiveness to suggestion or even discount the concept of suggestibility altogether.

What Else Improves Suggestibility?

Is there anything more we can pull from the academic literature that has been proven to increase suggestibility?

Unfortunately, it’s far easier to show what has been proven to not increase suggestibility. This blog post on myths and misconceptions provide the most accurate overview.

Looking at all the recent papers, there are ways to improve general suggestibility beyond what has already been mentioned. We can look at specific techniques of the people who are the best at hypnosis, and we can practice exercises that are hypnosis-adjacent to encourage different patterns of thought.

Neurofeedback appears to be a way to increase suggestibility, although I suspect that any focused interoception would produce the same results.

It’s possible to manipulate the environment such that people think a hypnotic suggestion is working. you can take a lightbulb and change the color very slightly and convince people that their perception is changing in response to hypnotic suggestion. This will cause them to be more responsive to other suggestions in general, even after telling them how it worked. This approach appears to work well even without a hypnotic context and can be attributed to pavlovian conditioning.

Another possible technique is to let the hypnotee provide their own suggestions. One paper (I cannot find it right now) related the story of a woman, given the suggestion that she could not speak because words wouldn’t come out, instead gave herself the suggestion that a man was choking her. Giving the hypnotee a suggestion to provide the most effective suggestion does seem like cheating, but it importantly gives the hypnotee some creative freedom and agency in suggestions.

Most people fail "Simon Says" because it requires response inhibition against expectancy. A good suggestibility maximizer would be one that adds ambiguity, lowers inhibition, and increases impulsivity: in short, alcohol. The study involved around 5 glasses of wine over 30 minutes for a 70kg (154lb) person, which frankly sounds like overkill if all you want to do is fuzz perception a bit. For recreational purposes, I’d say one glass of wine during the pre-talk is fine.

A recent study found that people with lower responsiveness may benefit from tDCS, but it was ineffective on medium-high responsiveness and this is not a DIY activity.

Oxytocin was found to increase the level of hypnotic responding in low hypnotizable people, probably due to increase in rapport.

I have not seen research into how exercises like wake-initiated lucid dreaming or imagination based activities like improv classes could alter baseline suggestibility, but I suspect any activity that encourages flexible perception and exercising belief would help.

More directly, this paper looked the research on the effectiveness on hypnotic inductions. One of the recommendations was the finding that increase absorption and reduce critical thinking, with endearingly clunky suggestions like "Allow yourself to let go completely … don’t question what you’re being asked to do and experience … just go with the flow" and "Allow yourself to feel completely focused … let your attention narrow down … focus only on the things I say … and the things I ask you to experience and do."

Further Reading

If you’re interested in learning more about hypnosis, an overview of other theories of hypnosis is on Hypnosis and Suggestion, and an overview of the field is here. A good academic history is on Cosmic Pancakes.

I also recommend this video by Irving Kirsch:

Vreahli has a comprehensive website at yourinductionsucks.fyi that has notes on a number of hypnosis books and papers.

Summary

It’s okay if much of this doesn’t make sense right now. All you need to remember is that there are three main components: rapport, expectancy, and imagination. A good hypnosis session that maximizes all three components involves good negotiation and a good pre-talk before the induction itself.