Neuro Linguistic Programming

Neuro Linguistic Programming (NLP) is not a part of the newbie guide, but I don’t want you to think that I am not including NLP because I don’t think it’s significant or useful.

The blunt truth is that, for the purposes of performative hypnosis, it doesn’t matter whether NLP is gospel truth or meretricious garbage. NLP is a vibe. A trope. It’s hypnosis kayfabe. It doesn’t need to be taken seriously or literally for you to have fun with it in whatever way you want. If you are concerned that you are just copying NLP without fully understanding it then I can reassure you that you are doing it right: NLP is based primarily on copying techniques without understanding them.

As I am an unrepentant nerd, I’m going to give you the story of NLP from a clinical hypnosis perspective, decade by decade, through books and papers. I owe thanks to Donald Clark for some of the incidental references.

If you think I’ve missed anything or have an extra paper or perspective to add, you can contact me through the feedback page.

1970s

The origins of NLP came from Bandler’s experience transcribing audio tapes of Virginia Satir and Fritz Perls while working at a bookstore, where he became familiar with their speech patterns to the point where he could be mistaken for Perls on occasion. Bandler practiced in workshops by mimicking Perls in his "Gestalt class" — although according to Michael Hall, he did not understand the history behind Gestalt, despite being involved in publishing The Gestalt Approach & Eye Witness To Therapy.

According to Terrence McClendon, Bandler first started teaching Gestalt Awareness at UC Santa Cruz as a seminar instructor. Bandler would play the Gestalt Therapist and direct students to become aware of what they were seeing, hearing, and feeling, working through psychodrama and open chair techniques. He also taught weekend workshops that were not affiliated with the university, and charged weekly group fees. The "meta model" that formed the core of NLP was formed from repeated workshops within a small group "watching and listening to video and audio tapes and transcripts of Virginia Satir and Fritz Perls."

It’s not clear where many of the initial NLP claims originated. Bandler is vague on his sources, and even then it’s not clear that Bandler’s reporting is accurate. In Memories: Hope is the Question Bandler does discuss that eye accessing was pulled from a neurological journal (probably Neisser and Hebb’s eye movement replay theory), the eye rolling of college students who were asked what they thought of the White House, and Betty Boop cartoons.

OF: Representational systems and accessing cues - could you tell us a little about your earliest memories of your experiences with these?

RB: Well, accessing cues were there all along. I read an article in this neurological journal in which they were studying perception and how the eyeballs move when you’re looking at something. They found that when they asked people to recall an image of a white house [sic] that they showed them, the person’s eyes usually shifted up to the left and the researcher said this must mean something. […] Really, though, you could see accessing cues in Betty Boop commercials and cartoons from the 1920s and 30s. Everybody’s kind of known about it and people responded to it as if it was there.

Despite Grinder’s involvement as a college professor, there is no indication that they ever attempted to submit a proposal to validate their theories or involve the larger academic community. The repeated workshops with a core group and the emotionally intense nature of the sessions (along with Bandler’s cocaine habit) meant that the group as a whole was attuned to Bandler and let him engage in behavior that would have been broadly unacceptable.

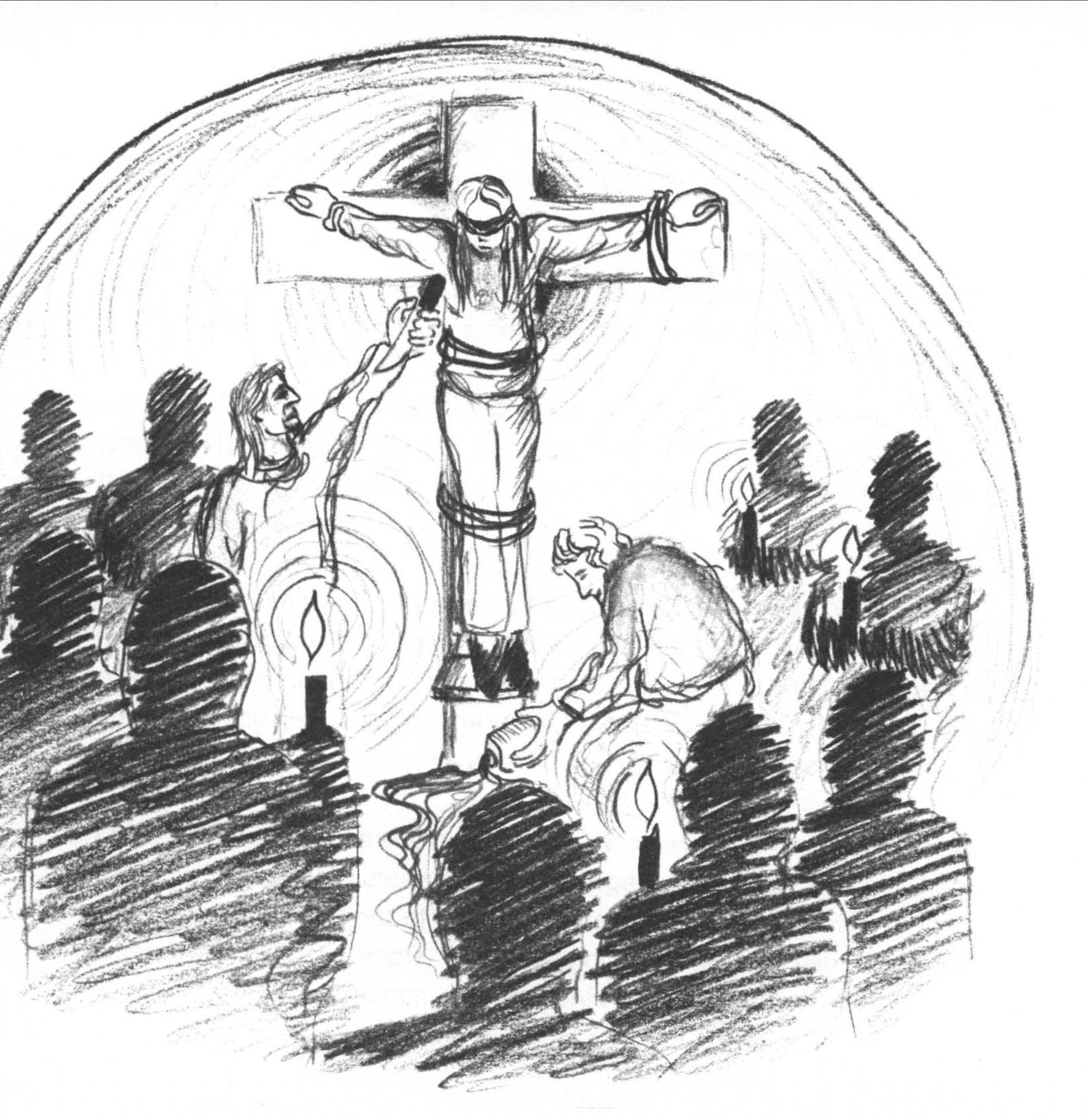

McClendon provides an anecdote that gives a sense of how the group’s norms were skewed as Bandler’s influence grew. The NLP group ended with a Christmas party in 1975 with Bandler staging an event: one of the women in the group, Devra, was promised a present by Bandler. She was sent out of the room and was blindfolded in anticipation of the surprise.

We were instructed to stand around in front of the cross and hold our candles in front of us. Devra was led out blindfolded and was then tied onto the cross. John then put some lighting fluid at the bottom of the cross and proceeded to set it ablaze. Devra at this time began to smell smoke and was wondering what was going on. She started sounding anxious about the situation asking, "What is going on?". Richard asked her if she would like to have her gift now. She said she would and so Richard took her blindfold off and gave her a knife which she could then use to cut herself off the cross.

To this day I don’t think that Devra has ever forgiven Richard. I have heard that she is still plotting on how to get back at him. Richard did have a serious discussion with her after about how she could learn from the experience, however I don’t think she was listening.

What stands out is that the group didn’t question or push back on this behavior, and there is no discussion of Bandler facing any kind of social or legal consequences for this stunt. Whatever experiments Bandler was conducting with the group, it’s already clear at this point the group was going to validate and confirm whatever theories Bandler proposed.

The first books on NLP, co-written with Grinder, were the Structure of Magic 1 and Structure of Magic 2 books published in 1975 and 1976, when he was only 25. Neither Bandler nor Grinder had credentials in therapy, with Bandler still an undergrad and Grinder being a linguist and "a novice at that time in the applications of counseling and psychotherapy."

By the late 1970s, Bandler and Grinder started marketing NLP as a business tool according to Mother Jones in an article called The Bandler Method, teaching salespeople to establish rapport by mirroring body language. I recommend going through the Mother Jones article in its entirety, it is a read and makes it clear that Bandler’s behavior in his NLP group was not an isolated event. If the scanned PDF is awkward to read, Jason Youv transcribed it to Medium.

In February 1979, 150 students paid $1000 each for a 10 day workshop, and Bandler and Grinder started turning those transcripts into books, resulting in Frogs Into Princes. From the age of roughly 30, Bandler started on his full time career: teaching NLP.

1980s

The scientific community first took note of NLP around 1980, with Test of the eye-movement hypothesis of neurolinguistic programming. This study found "[r]esults do not support the hypothesis, although eye-movement responses were not random."

The preferred modality by which 50 right-handed female college students encoded experience was assessed by recordings of conjugate eye movements, content analysis of the subject’s verbal report, and the subject’s self-report. Contrary to the prediction of the theory of neurolinguistics programming (NLP), kappa analyses failed to reveal any agreement of the three assessment methods. In addition, each assessment method was shown to be biased toward revealing a particular representational modality. The application of certain principles of NLP in counseling settings was therefore questioned.

In 1984, Sharpley reviewed the various papers that investigated the preferred representational system (also known as VAKOG) Predicate matching in NLP: A review of research on the preferred representational system and found no support. From the summary:

The increasing publicity of Neurolinguistic Programming (NLP) has not been accompanied by marked research support. As a first review of the 15 studies performed so far that have investigated the use of the Preferred Representational System (PRS) in NLP, this article describes each of these studies, compiling a summary of data collected. Aspects of design, methodology, population, and dependent measures are evaluated, with comments on the outcomes obtained. Results of this review suggest that there is little supportive evidence for the use of the PRS in NLP in these 15 studies, with much data to the contrary. Questions of accountability are raised, with suggestions for future research.

There were a number of follow up papers in 1985, all showing results that did not support Bandler and Grinder’s work.

Neurolinguistic programming’s hypothesized eye-movements were measured independently from videotapes of 30 subjects, aged 15 to 76 yr., who were asked to recall visual pictures, recorded audio sounds, and textural objects. Chi square analysis indicated that subjects' responses were significantly different from those predicted. When chi square comparisons were weighted by number of eye positions assigned to each modality (3 visual, 3 auditory, 1 kinesthetic), subjects' responses did not differ significantly from the expected pattern. These data indicate that the eye-movement hypothesis may represent randomly occurring rather than sensory-modality-related positions.

"Visual responses were as frequent as auditory responses which is contrary to the current thinking that visual responses predominate. These results are not consistent with previous research (Thomason, et al., 1980), except that neither project supported the eye-movement hypothesis of neurolinguistic programming."

Mental imagery as revealed by eye movements and spoken predicates: A test of neurolinguistic programming showed no support for the model:

Bandler and Grinder’s proposal that eye movement direction and spoken predicates are indicative of sensory modality of imagery was tested. Subjects reported on modality, sequence, and vividness of images to questions that evoked either no images or visual, auditory, or kinesthetic images. Eye movement direction and spoken predicates were matched with sensory modality of the questions. Subjects reported images in the three modes, but no relation between imagery and eye movements or predicates was found. The visual modality was dominant. Visual images were most vivid and often reported. Most subjects rated themselves as visual, and most spoken predicates were visual. These data are discussed within the context of an ever-growing literature that does not support Bandler and Grinder’s model and in the context of the difficulties in interpreting the model itself.

In 1985, Double hypnotic induction: An initial empirical test tried the double ("dual") induction with negative results:

In separate experimental sessions, 34 undergraduate students experienced audiotapes of a standard hypnotic induction and a double induction similar to that described by Bandler and Grinder (1975). In the double induction, subjects heard a hand-levitation induction through the ear that is contralateral to the dominant cerebral hemisphere and, simultaneously, heard grammatically childlike messages through the other ear. Half of the subjects experienced the double induction first. There were no significant within-subject differences between the two inductions. However, subjects who experienced the double induction prior to the standard induction were significantly less responsive to suggestions following both inductions, which suggests that the double induction as a first experience of hypnosis may have a negative impact on subsequent experiences of hypnosis.

Neuro-linguistic programming treatment for anxiety: Magic or myth? found that their claim to cure anxiety in a single session was not accurate:

The neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) treatment for anxiety, claimed to be a single-session cure for unpleasant feelings, was compared with self-control desensitization of equal duration and a waiting-list control group in treating public speaking anxiety. Fifty-five speech-anxious undergraduates underwent pretreatment and post treatment assessments of anxiety during 4-min speeches. The results indicate that neither treatment was more effective in reducing anxiety than merely waiting for 1 hr. These data suggest that Bandler and Grinder’s (1979) claim for a single-session cure of anxiety may be unwarranted.

In 1986, Bandler made a rare statement. According to Wikipedia "at a meeting with Richard Bandler in Santa Cruz, California, on July 9, 1986, the [National Research Committee] influence subcommittee… was informed that PRS was no longer considered an important component of NLP. He said that NLP had been revised." It’s not known whether this was in response to the research, but it did not appear to help his case.

In 1987, there were two papers on NLP reviewing the available research, from Sharpley and Heap. It’s about this time that you can see the desire to wrap things up.

Research findings on neurolinguistic programming: Nonsupportive data or an untestable theory? says that further study of NLP is not going to prove anything new:

One may conclude that there is little use to the field of counseling research in further replications of previous studies of the principles underlying NLP. In 44 studies of these principles, they have been shown to be without general support from the data. Future research that can contribute new data on this issue via methodological advances or consideration of different aspects of NLP may be justified, but perhaps of more relevance (and value) now would be a careful metaanalysis of the large amount of data already gathered. Elich et al. (1985) referred to NLP as a psychological fad, and they may well have been correct. Certainly research data do not support the rather extreme claims that proponents of NLP have made as to the validity of its principles or the novelty of its procedures.

Neurolinguistic Programming - An Interim Verdict looks at PRS and eye movements and says "if these claims fare no better than the ones already investigated, then the final verdict on NLP will be a harsh one indeed."

Heap followed up in 1988 with Neuro-Linguistic Programming - A British Perspective:

The assertions and therapeutic claims of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) are overviewed, as well as its impact and status in Britain. It is noted that most of the experimental investigations on NLP have concerned the assumptions relating to the idea of representational systems, their proposed relationship to predicate usage and eye movements, and the presumed benefits of matching in any of these ideas. The limited number of studies of the efficacy of therapeutic procedures described by NLP practitioners have failed to demonstrate their alleged potency. Comparisons are drawn between NLP and Ericksonian therapy and alternative medicine. It is speculated that they may be more usefully understood as cultural phenomena.

And from there, the dominos start to fall.

In 1988, the United States National Research Council produced a report, overseen by a board of 14 academic experts, stating in Enhancing Human Performance:

Individually, and as a group, these studies fail to provide an empirical base of support for NLP assumptions…or NLP effectiveness. The committee cannot recommend the employment of such an unvalidated technique […] instead of being grounded in contemporary, scientifically derived neurological theory, NLP is based on outdated metaphors of brain functioning and is laced with numerous factual errors.

In 1989, Weitzenhoffer in The Practice of Hypnotism, Volume 2 devotes an entire chapter to the Bandler/Grinder interpretation of hypnosis, including a discussion on exactly what and how NLP has taken from psychology and what has been renamed and repackaged.

Weitzenhoffer points out:

NLP proper, as originally developed in Structure of Magic I and II (1975, 1976) has nothing to do directly with hypnotism. It is not about hypnotism, and its only relationship to it is that the Bandler/Grinder interpretation of Ericksonian hypnotism grows out of their use of the same linguistic type of analysis to elucidate the mechanism or action of communications done in the contexts of psychotherapy and hypnosis.

One way that NLP attempts to bolster itself is by attaching other parts of psychology to it, often changing the name. Weitzenhoffer is particularly critical here. For example, he calls out anchoring:

An anchor can be said to be any stimulus that consistently evokes the same response from an individual. The specific process of anchoring is the deliberate association by an operator of a stimulus with a particular experience the subject is having for the purpose of eliciting it on subsequent occasions using this stimulus. For example, the patient is asked to think back to a situation when he was experiencing certain feelings that the therapist wants to use. When the patient indicates that he is reliving the feelings, the therapist touches a part of his body in a specific way. According to Bandler and Grinder, any time the therapist again touches the patient in exactly the same way, the feelings will be reinstated. Anchoring is clearly nothing more than making use of the process that Erickson referred to as redingretation.

And even then, Weitzenhoffer questions whether anchoring has enough supporting data behind it:

Anchoring, which clearly is not specific to the use of hypnotism, has had great appeal because of its apparent simplicity and because of the quasi-magical therapeutic effects that Bandler and Grinder claim can be obtained with it. In standard psychological terms, it amounts to one-trial learning or conditioning through contiguity successfully taking place in a far wider variety of circumstances and with remarkably far greater effectivity than would be expected from available laboratory data. Aside from the beliefs of Bandler, Grinder, and their students that anchoring techniques work, there are little supporting data. It must be admitted that, when viewed superficially, demonstrations of anchoring given by Bandler and Grinder at their workshops have been at times quite impressive. However, when closely examined, they have shown themselves to be far less impressive, and at times to be questionable, demonstrations. In any event, as far as Erickson’s work is concerned, he did not speak of anchoring per se, and, to the extent he may have used it, he did not do so in the ways detailed by Bandler and Grinder. They, it seems, can be given credit for having been innovative in its uses.

Weitzenhoffer also calls out reframing:

The term "reframing" seems to have recently gathered a fair amount of popularity among therapists not identified with NLP. They mostly use it to designate any intervention aimed at changing the internal responses of an individual to a situation or to his behavior, either by modifying the meaning the person gives to the situation or behavior, or by finding a context in which the behavior becomes acceptable. A new perspective is thus created that is said to "reframe" the events and that, presumably, eventually enables the patient to produce different responses. There is, of course, nothing new in this; therapists were doing this long before NLP came into existence.

After going through a thorough review of NLP, he starts off the discussion and critique:

More than 10 years after its birth, NLP does not appear to have made an appreciable impact upon the behavioral. sciences, and its success seems to have been primarily that of a therapeutic fad. Despite its creators' constant direct and indirect infantile references and allusions to magic, wizards, enchantments, and and so on (possibly in a metaphorical way), there is little evidence that it has lived up to the many promises it has made of providing magical solutions for ailing mankind.

[…] The major weakness of Bandler and Grinder’s linguistic analysis is that so much of it is built upon untested hypotheses and is supported by totally inadequate data.

[…] Has NLP really abstracted and explicated the essence of successful therapy and provided everyone with the means to be another Whittaker, Virginia Satir, or Erickson? Quite apart from the above remarks, its failure to do this is evident because today there is no multitude of their equals, not even another Wittaker, Virginia Satir, or Erickson. Ten years should have been enough time for this to happen. In this light, I cannot take NLP very seriously. […]. Patterns I and II are poorly written works that were an overambitious, pretentious effort to reduce hypnotism to a magic of words. This clearly has not paid off.

Finally, Weitzenhoffer concludes:

I would not want the reader to leave this discussion with the idea that NLP, and particularly its view of Ericksonian hypnotism, should be altogether disregarded, or that linguistics has nothing to contribute. There may be some golden nuggets to be found among the dross. […] The point is to extract what is useful and to disregard the rest.

1990s

After this point, NLP was not considered seriously by the clinical or scientific communities.

In 1990, Efran and Lukens state:

[O]riginal interest in NLP turned to disillusionment after the research and now it is rarely even mentioned in psychotherapy.

In 1997, Von Bergen et al detailed the decline of interest in NLP:

The most telling commentary on NLP may be that in the latest revision of his text on enhancing human performance, Druckman omitted all references to Neurolinguistic Programming.

2000s

By the early 2000s, NLP was considered to be a pseudoscientific fad.

NLP is a scientifically unsubstantiated therapeutic method that purports to “program” brain functioning using a variety of techniques, including mirroring the postures and nonverbal behaviors of clients.

By the second edition of the book in 2014, NLP is mentioned on page 3 as an aside.

To end where I began — NLP is no longer as prevalent as it was in the 1970s and 1980s, but is still practised in small pockets of the human resource community today. The science has come and gone yet the belief still remains.

In 2006, Discredited psychological treatments and tests: A Delphi poll found NLP to be given similar ratings as dolphin-assisted therapy, equine-assisted therapy, psychosynthesis, scared straight programmes, and emotional freedom technique.

In 2006, The Guardian attends an NLP conference with Richard Bandler and Paul McKenna. Some highlights from the article, especially interesting in Bandler’s discussion of the origins of NLP:

He and McKenna have made particular headway in the business world. In fact, Ian Aitken, managing director of McKenna’s company, says the individuals looking for a cure for their phobias are now in the minority. I ask him what is it about NLP that attracts salespeople. Bandler, he replies, teaches that everyone has a dominant way of perceiving the world, through seeing, hearing or feeling. If a customer says, "I see what you mean," that makes them a visual person. The NLP-trained salesperson will spot the clue and establish rapport by mirroring the language.

[…]

I go home. I don’t think I have ever, in all my life, had so many people try to keep me in order in one single day. Advocates and critics alike say attaining a mastery of NLP can be an excellent way of controlling people, so I suppose the training courses attract that sort of person. Ross Jeffries, author of How To Get The Women You Desire Into Bed, is a great NLP fan, as is Duane Lakin, author of The Unfair Advantage: Sell With NLP! (Both books advocate the "that feels good to me" style of mirroring/rapport building invented by Bandler.) But still, the controlling didn’t work on me. Nobody successfully got inside my head and changed - for their benefit - the way I saw NLP. In fact, quite the opposite happened. This makes me wonder if NLP even works.

Over the days that follow, things start to improve. I corner McKenna and tell him his assistants are driving me crazy. "You have to make them leave me alone," I say. He looks mortified, and says they’re just overexcited and trying too hard. But, he adds, the course would be a lot worse without them energising the stragglers into practising NLP techniques on one another.

[…]

[Bandler] was diagnosed as a sociopath. "And, yeah, I am a little sociopathic. But my illusions were so powerful, they became real - and not just to me." He says NLP came to him in a series of hallucinations while he was "sitting in a little cabin, with raindrops coming through the roof, typing on my manual typewriter". This was 1975. By then he was a computer programmer [sic: this is not accurate, The Bandler Method says his only career has been NLP and Bandler has frequently lied about his personal and professional life], a 25-year-old graduate of the University of Santa Cruz.

It’s surprising to me that Bandler would cheerfully refer to NLP as a sociopathic hallucination that struck a chord with the business world. I’m not sure he’s ever been that blunt about it before. But I suppose, when you think about it, there is something sociopathic about seeing people as computers who store desires in one part of the brain and doubts in another.

"See, it’s funny," he says. "When you get people to think about their doubts, notice where their eyes move. They look down! So, when salespeople slide that contract in, suddenly people feel doubt, because that’s where all the doubt stuff is."

In 2006, Derren Brown published Tricks of the Mind. He wrote about NLP and his experience.

After about six years of familiarity with the techniques and attitude of NLP, and in a moment of unpleasant madness, I thought I might become a hypnotherapist full-time, and it seemed proper that I acquire some relevant qualifications. To do so, I attended an NLP course, given by Bandler and others, and achieved the relevant 'Practitioner' qualification. The course, perversely, put me off that career rather than cementing my ambition. I now have a lot of NLPers analyzing my TV work in their own terms, as well as people who say that I myself unfairly claim to be using NLP whenever I perform (the truth is I have never mentioned it). To confuse things even further, it has recently made a home for itself as a fashionable conjuring technique of dubious efficacy.

[…] The course I attended was large (four hundred people) and highly evangelical in its tone. It reminded me a lot of the Pentecostal churches I had attended a few years earlier. Although I enjoyed much of the course and certainly got into the swing of it, the parallel with the church made me uncomfortable at times. One manipulative technique I found in both was the "we can laugh at ourselves" mentality. NLP gurus or the happy clappy leaders of a charismatic church will sometimes stand on stage and encourage their congregations to have a good old chuckle as they themselves parody the nuttier excesses of their respective scenes; and as everyone laughs in response, any quiet reserve of intelligent skepticism in the room dissolves to nothing, and the scene is made safer and free from dissent.

[…] At the end of my course, which lasted only four days, I was given the Practitioner certificate. I didn’t have to pass any tests or in any sense 'earn' my qualification. In many ways the course was about installing a 'go for it' attitude towards changing oneself or others for the good, so somehow, any formal test would have seemed disappointingly pedestrian. So the four hundred or so delegates, some of whom were clearly either unbalanced or self-delusory, were set free after a highly evangelical four-day rally to potentially set themselves up as therapists and deal with broken people under the banner of NLP. We were told that after a year we should contact the organization and tell them why we should have our license renewed. If we had been using our NLP creatively, they would send another certificate for a second year of practice. Because spending those few days in the company of hundreds of would-be NLPers had put me off ever practicing it as a profession, I didn’t think to contact the organizers again. But after a year or so I got a letter reminding me to call them to talk about sorting out a new certificate. I ignored it, but a short while later received another communication saying that they would be happy to send me one anyway if I would get back in touch. The ease with which they were happy to dish out their certificates struck me as suspect, and again I ignored their request. Not long after that, a nice new unsolicited certificate dropped through my letterbox, qualifying me for another year of practice.

In 2008, Heap wrote again in The Validity of Some Early Claims of Neuro-Linguistic Programming on the continuing popularity of NLP among the lay public:

I believe that the following impressions are also likely to be reliable.

NLP continues to make no impact on mainstream academic psychology.

NLP has made only limited impact on mainstream psychotherapy and counselling.

NLP remains influential amongst private psychotherapists, including hypnotherapists, to the extent that they claim to be trained in NLP and ‘use NLP’ in their work.

NLP training courses abound and NLP now seems to be most influential in management training, lifestyle coaching, and so on. Particularly with reference to this, the term ‘growth industry’ appears to be apposite.

I know little about this last-mentioned area of work but I am intrigued by this gradual extension of NLP beyond psychotherapy. This may have something to do with the fact that the supply side of the market for psychological therapies looks pretty much saturated and the major potential customer in the UK at least, namely the National Health Service, tends to favour a limited range of products, notably those that are labelled ‘evidence based’. The same appears to be true for medical insurance arrangements in the USA. When I say ‘customer’ I mean not just clients and patients wanting help, but also people wanting to train as therapists (or develop their existing repertoire of skills). My impression is that the extension of NLP into management training, etc. is all to do with finding wider markets for its products (and packaging and repackaging its products to suit those markets).

Like most of what we do, much of it comes down to money in the end.

In 2009, Neuro-linguistic programming: cargo cult psychology? likewise determines that NLP has no scientific basis:

NEURO-LINGUISTIC programming (NLP) is a popular form of inter-personal skill and communication training. Originating in the 1970s, the technique made specific claims about the ways in which individuals processed the world about them, and quickly established itself, not only as an aid to communication, but as a form of psychotherapy in its own right. Today, NLP is big business with large numbers of training courses, personal development programmes, therapeutic and educational interventions purporting to be based on the principles of NLP. This paper explores what NLP is, the evidence for it, and issues related to its use. It concludes that after three decades, there is still no credible theoretical basis for NLP, researchers having failed to establish any evidence for its efficacy that is not anecdotal.

In 2009, The Independent interviews Bandler and attends his course in Messing with your head: Does the man behind Neuro-Linguistic Programming want to change your life – or control your mind?.

Each day of the course, Bandler leads the morning session with a demonstration and a talk (Grinder is long since out of the picture; the pair acrimoniously parted ways following a bitter copyright lawsuit in 1997 – proof that even NLP experts don’t have solutions for everything). At 10am on the dot, the hotel conference-room doors open to a loud blast of emphatically upbeat synth music: our call to action. As students amble towards their seats, some do jiggly little dance steps, others clap to the beat; there are sporadic whoops of enthusiasm. Of the 100-odd here for the course, people have travelled from as far afield as England, Japan, Australia, Turkey and Baghdad. Others have volunteered to be course assistants, paying their own flights and accommodation, just to be close to Bandler. (Which is not all that surprising when one considers that "students" can pay up to £10,000 for one of his intimate, three-day courses.)

In 2009, Brian Dunning in his Skeptoid podcast reviewed NLP:

I’ve read a fair amount about NLP, and my analysis of the Meta Model is pretty simple. I’d describe it as a confrontational manner of speaking intended to dominate a conversation by nitpicking the other’s persons sentences apart. For example, if it’s a good day and all is well, I might be inclined to make an offhand, general comment like "I feel pretty good today." The Meta Model response to that is "What specifically makes you feel good?" And, I don’t really know. I don’t really have a single, specific answer. And whatever I do come up with gets attacked the same way: "Exactly why does that make you feel good?" And suddenly I’m on the defensive; I’m being made to feel that I’m in error, the position I’ve taken is revealed to be unsupported; and I’m now putty in the NLP guy’s hands. Basically, it’s being a condescending jerk in the way you talk to someone, in order to exert influence. That’s the Meta Model. It’s not psychotherapy; it’s high-pressure sales. The Milton Model takes a different road to the same destination: low-pressure sales.

And it’s not just sales. It’s negotiation in business. It’s gaining the upper hand in interpersonal relationships. It’s being an effective manager or sports coach. But — and this is the big "but" — despite the claims of those who sell NLP books and seminars, it is not part of modern psychotherapy. Russia and the UK do have professional associations of NLP practitioners, but these are composed largely of people selling books and seminars, and only rarely of credentialed psychiatrists.

2010s

In 2010, Witkowski wrote Thirty-five years of research on Neuro-Linguistic Programming (DOI: 10.2478/v10059-010-0008-0 but the URL to https://journals.pan.pl/dlibra/publication/114591/edition/99644/content is dead). If you read one paper on NLP, read this one: this goes over all the research at once that was listed in the "NLP database" supposedly proving the effectiveness of NLP.

The abstract gives a very sterile view of the paper:

The huge popularity of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) therapies and training has not been accompanied by knowledge of the empirical underpinnings of the concept. The article presents the concept of NLP in the light of empirical research in the Neuro-Linguistic Programming Research Data Base. From among 315 articles the author selected 63 studies published in journals from the Master Journal List of ISI. Out of 33 studies, 18.2% show results supporting the tenets of NLP, 54.5% - results non-supportive of the NLP tenets and 27.3% brings uncertain results. The qualitative analysis indicates the greater weight of the non-supportive studies and their greater methodological worth against the ones supporting the tenets. Results contradict the claim of an empirical basis of NLP.

But read the paper itself:

While conducting my analysis I noted a certain historical aspect of NLP supportive research. As I realized, most of the research was carried out in the 1980s and partially in the 1990s. In the subsequent years, the number of such research studies decreased and they concerned secondary aspects of the concept or were performed based on the assumption that the fundamental principles of NLP are true. The world of science was apparently losing its interest in the concept of Bandler and Grinder, having confronted it with the research findings. The concept’s proponents lacked motivation to undertake any type of research into, for instance, the effectiveness of its methods.

About the NLP database itself:

The number of theoretical studies in the base, such as polemics, dissertations, and discussions is so high that referring to it as to the Research Data Base is considerable misinterpretation as well. What is even stranger is the fact that works completely unrelated to NLP are added to the base. While reading such articles I strengthened my belief that it was only due to some single key words that the NLP related status of those papers was approved. This gives rise to the suspicion that even the database administrators do not read articles, not to mention the abstracts.

All of this leaves me with an overwhelming impression that the analyzed base of scientific articles is treated just as theater decoration, being the background for the pseudoscientific farce, which NLP appears to be. Using “scientific” attributes, which is so characteristic of pseudoscience, is manifested also in other aspects of NLP activities. It is primarily revealed in the language – full of borrowings from science or expressions referring to it, devoid of any scientific meaning. It is seen already in the very name neuro-linguistic programming - which is a cruel deception. At the neuronal level it provides no explanation and it has nothing in common with academic linguistics or programming. Similarly impressive sounding and similarly empty are expressions used for formulation of tenets of the concept, such as sub-modalities, pragmagraphics, surface structure, deep structure, accessing cue, and non accessing movement.

My analysis leads undeniably to the statement that NLP represents pseudoscientific rubbish, which should be mothballed forever. One may even come to believe that my analysis was a vain effort after all. It yielded the same conclusions as the ones arrived at by Sharpley (1984, 1987), Heap (1988) and others. Without doubt, NLP represents big business offering and tempting people with amazing changes, personal development and, what is worst, therapy. In this respect the analysis is an update of the state of knowledge on the subject by reviews published in the period after the latest analyses. Furthermore, it also provides arguments sufficient to answer the following ethical question: Is using and selling something nonexistent and ineffective ethical?

And finally the conclusion:

The analysis of the NLP Research Data Base (state of the art) by all measures was like peeling an onion. To reach its core, first I had to remove some useless layers, and once I arrived, I was close to tears. Today, after 35 years of research devoted to the concept, NLP reminds one more of an unstable house built on the sand rather than an edifice founded on the empirical rock. In 1988 Heap passed a verdict on NLP. As the title of his article indicated, it was an interim one. In the conclusions he wrote: If it turns out to be the case that these therapeutic procedures are indeed as rapid and powerful as is claimed, no one will rejoice more than the present author. If however these claims fare no better than the ones already investigated then the final verdict on NLP will be a harsh one indeed (p. 276). I am fully convinced that we have gathered enough evidence to announce this harsh verdict already now.

Witkowski follows up with a brief summary in A review of research findings on neuro-linguistic programming. The conclusion:

Today, after 35 years of research into the model, NLP reminds one more of an unstable house built on sand rather than an edifice founded on a solid empirical foundation. In the title of his 1987 review of NLP, Sharpley posed a question: "nonsupportive data or untestable theory?" A year later Heap passed an "interim" verdict on NLP, as did Baddeley the following year. Given the amount of research that has been conducted on NLP in the subsequent decades, perhaps the time has come to render a more definitive conclusion.

A virtue of science is the ability to test all hypotheses, even the most implausible ones. If, however, scientists focused their interest ad infinitum on those hypotheses that continually failed to find support, the enterprise would soon lose its raison d’être. The present review suggests that enough evidence has been collected to announce a final verdict now: NLP is ineffective both as a model explaining human cognition and communication, and as a set of techniques of influence and persuasion.

In 2010, Evidence-Based Practices in Addiction Treatment: Review and Recommendations for Public Policy identified NLP as "certainly discredited" along with "Scared Straight" and past-life therapy.

Proponents of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) claim that certain eye-movements are reliable indicators of lying. According to this notion, a person looking up to their right suggests a lie whereas looking up to their left is indicative of truth telling. Despite widespread belief in this claim, no previous research has examined its validity. In Study 1 the eye movements of participants who were lying or telling the truth were coded, but did not match the NLP patterning. In Study 2 one group of participants were told about the NLP eye-movement hypothesis whilst a second control group were not. Both groups then undertook a lie detection test. No significant differences emerged between the two groups. Study 3 involved coding the eye movements of both liars and truth tellers taking part in high profile press conferences. Once again, no significant differences were discovered. Taken together the results of the three studies fail to support the claims of NLP. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

In 2012, Neurolinguistic programming: a systematic review of the effects on health outcomes takes a look at NLP from the perspective of the NHS focus of evidence based outcomes:

NLP’s position outside mainstream academia has meant that while the evidence base for psychological intervention in both physical and mental health has strengthened, parallel evidence in relation to NLP has been less evident and has attracted academic criticism. No systematic review of the NLP literature has been undertaken applying Cochrane methods. The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic literature review and appraise the available evidence for effectiveness of NLP on health-related outcomes.

and concludes:

There is little evidence that NLP interventions improve health-related outcomes. This conclusion reflects the limited quantity and quality of NLP research, rather than robust evidence of no effect. There is currently insufficient evidence to support the allocation of NHS resources to NLP activities outside of research purposes.

In 2013, Neuro-linguistic programming. Still top of the pops after 40 years used the phrase "jackdaw epistemology" to describe NLP’s unhelpful habit of reappropriating research under the NLP umbrella:

[T]he criteria for an NLP model are explicitly stated by John Grinder and his training partner Carmen Bostic St Clair to this day as they conduct NLP trainings:

A sensory-grounded description of the elements in the pattern and their critical ordering.

A sensory-grounded description of what consequences the practitioner can anticipate through a congruent application of the pattern. (one could replace ‘anticipate’ with ‘predict’ here.)

the identification for the conditions or contexts in which the selection and application of this pattern is appropriate. (Bostic St Clair & Grinder, 2001, p.351)

A definition of NLP which I believe does describe the above very well is: ‘An attitude with a methodology which leaves behind a trail of techniques.’ the attitude can be interpreted as the pre-suppositions of NLP which, according to Tosey and Mathison (2009), come mainly from systems theory, the methodology is modelling and the techniques are the NLP models which are essentially a collection of NLP patterns derived from NLP modelling projects. examples of well-known NLP presuppositions which are implicitly regarded as the theoretical base of NLP are such axioms as, ‘the mind and body are part of one system’; ‘the map is not the territory’; ‘behind every behaviour there is a positive intention’, ‘the client already has the resources to make the necessary changes’.

In my review of the NLP literature to date I concluded that no NLP model which accords with the above criteria actually exists (Grimley, 2013, p.171).

The founders of NLP explicitly stated that NLP ‘makes no commitment to theory, but rather has the status of a model – a set of procedures whose usefulness not truthfulness is to be the measure of its worth (Dilts et al, 1980). The challenge in researching NLP is that in practical terms it can be anything you wish and advocates of NLP seem keen to associate with any current research to market their ‘models’.

In 2014, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) conducted a review on Neuro-Linguistic Programming for the Treatment of Adults with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, General Anxiety Disorder, or Depression: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines:

What is the clinical effectiveness of NLP for the treatment of adults with PTSD, GAD, or depression?

The literature search did not find clinical evidence on NLP for the treatment of adults with PTSD, GAD, or depression

What are the guidelines associated with the use of NLP for the treatment of adults with PTSD, GAD, or depression?

Despite strong recommendations on the use of psychosocial therapies such as behavioural activation, cognitive behavioural therapy, interpersonal therapy, the guideline reported that no evidence on the use of NLP specific to depression and meeting guideline inclusion criteria was identified.

As NLP became more popular, some research was conducted and reviews of such research have concluded that there is no scientific basis for its theories about representational systems and eye movements.

The huge popularity of neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) over the past three decades has in some ways mirrored the growth in coaching psychology. This paper is part of a series of four papers in a special issue within ICPR that aims to explore NLP coaching from diverse perspectives, offering personal insights or reviews of evidence. As part of this process a pair of authors were invited to advance the case for and the case against NLP. This paper aims to adopt a critical stance; reviewing the concept of NLP, exploring the claims made by advocates and critically reviewing the evidence from a psychological perspective. In undertaking this review we completed a series of literature searches using a range of discovery tools to identify research papers, based on pre-determined search criteria. This review led us to the conclusion that unique NLP practices are poorly supported by research evidence.

And the paper concludes:

In this paper we aimed to review the evidence for NLP and specific for NLP coaching. Given this review, we have no hesitation in coming to the view that coaching psychologists and those interested in evidenced based coaching would be wise to ignore the NLP brand in favour of models, approaches and techniques where a clear evidence base exists. However, moving forward, we might take with us the dream of drawing together a unified model of coaching which brings the best of all approaches, but leaves the sales hype and unsubstantiated miracle change claims behind.

In 2022, Pseudoscience and Charlatanry in Coaching traces NLP back to its roots and starts pulling at loose threads. For example, the chapter looks at ethics:

In summary, confirmations of assumptions and intervention effects by scientific evaluation are missing, proving the fantastic effects they claim. This is remarkable, because NLP had originally started to increase the effectiveness following the models of the best therapists. Apparently, however, the resulting effects are rather lower and sometimes even negative. This is concealed by NLP representatives. Such withholding of negative research results is a severe violation of basic ethical scientific principles.

NLP’s attempts at mashing linguistic terminology into cognitive processes:

NLP uses Chomsky’s term “deep structure,” but refers to the unconsciously underlying rules and meanings (Grimley, 2008, p. 196 f.). This use distorts Chomsky’s linguistic theory, which only examines grammatical rules for transforming the underlying structures into the actual spoken or “surface” sentences. […] NLP refers to these basic terms of Chomsky, but uses them in a completely different way, without mentioning and explaining these differences. It seems mysterious why Grinder, as a linguist, could so completely distort the theory of Chomsky.

Stollznow (2014, p. 234) concludes that NLP “has very little to do with linguistics. (…) Yet, NLP claims to be heavily influenced by seminal linguist Noam Chomsky. In particular, NLP is said to be inspired by Chomsky’s theory of transformational grammar, and his concept of deep structure and surface structure in language (…). Other than borrowed terminology, NLP doesn’t bear a resemblance to any of Chomsky’s theories or philosophies.”

And the frequent confusion of anchoring with classical conditioning:

In NLP, anchoring’ is viewed as a “master tool.” Bandler and Grinder (1979) describe various scenes e.g. a consciously used physical touch of the shoulder of the client together with the request to imagine a successful coping with a difficult situation, assuming that this can activate a positive emotional state. This laying on of the hand is an example of “anchoring.” […] Grimley (2016, p. 175) in his recent description of NLP cites Derks (2000), who is very convinced that it is not necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of “anchoring,” since it is well confirmed by research on classical conditioning and completely identical to it: “For instance, instead of asking if the use of anchors is supported by scientific research, people wonder if ‘NLP’ is scientifically sound. But anchors are just another name for classical conditioning, something based on the Pavlovian paradigm” (Derks, 2000).

It may be possible in some cases that the described method, under conditions yet to be clarified, helps some people to remember intentions for action that are difficult to implement or to reinforce positive feelings of confidence. It is incomprehensible, however, why this method, which is so much propagated in NLP, is until today regarded as an application of classical conditioning according to Pavlov (cf. Grimley, 2016; Linder-Pelz, 2010). In experiments with humans, for example, it is possible to condition the eyelid blink reflex, if you accompany a short air blast to the eye, which stimulates the unconditional reflex to close the eye by a previous tone. By the way, such conditioning does not succeed in the same way in all people and requires a fixation of the head and 20–30 repetitions (Merrill et al., 1999). It is simply nonsensical to assume that positive coping with a difficult situation or “confidence” are “reflexes” which can be classically conditioned by means of a few repetitions of touches or even imaginations.

There’s some fun quotes about the annoyingly sloppy approach so prevalent in NLP.

More examples of jumbled technical terms and distorted references can frequently be found throughout the NLP literature. Conversely, it seems to be more difficult to find examples where Bandler and Grinder, or their followers, correctly quote technical terms and theories.

It is tragic that since the 1970s, NLP has quoted well-known scientists in such an associative, inaccurate, or distorting way, giving itself the appearance of a scientific approach. In itself, it does not take much expertise to recognize the differences between the original theories and their modification by NLP authors.

And finally, there is a summary that I’m going to quote in full because it’s so good.

NLP started in the 1970s as a promising new approach, which integrated new theories of the time and therapeutic methods of leading therapists. However, it is noteworthy that the effectiveness of NLP methods seems to be lower than that of the originals and that basic assumptions are not supported by research evidence. Research programs, or theories that have a smaller empirical support than their forerunners, are called “degenerative” by the well-known science philosopher (Lakatos, 1981). Compared to the high initial expectations, NLP must obviously be viewed as a “degenerated intervention approach” when compared to these earlier theories and methods.

In summarizing our evaluation against the criteria developed in this contribution, NLP should be classified as a “pseudoscience.” There is clear evidence that all four criteria apply to NLP from the founding years until today:

The claims of intervention methods with extraordinary effects are solely anecdotally supported by single cases or “experiences.”

Scientific confirmations of the assumptions and effects are missing and negative research results are withheld.

Scientific evaluation methods are rejected.

Scientific citations are imprecise or distorting.

There are, however, NLP proponents such as Linder-Pelz (2010) who strive for a scientific foundation and evaluation of the effectiveness of NLP. She herself criticizes the rejection of scientific research by the NLP community. From a future perspective, she demands an evidence-based, scientific NLP approach in the field of coaching. However, the standard formula that “more research is needed” would not suffice. The basic concepts, assumptions and intervention methods, and NLP training would have to be fundamentally reinvented.

Between a Conclusion and a Rant

The four-decade research trajectory reveals a clear pattern: initial scientific interest, systematic testing, consistent negative results, and eventual dismissal by mainstream academia. Over 300 studies were examined, with only 18% showing any support for NLP tenets, and those were of questionable methodological quality.

Brian Dunning and Michael Heap have an interesting take on NLP, oriented around sales and money. From this perspective, NLP can be described as a sales and marketing framework, oriented around conferences and promotional material. As in most sales frameworks, the biggest audience and the most money is oriented around the hopeful practitioners that want to make money with their NLP techniques — while these practioners are hoping to mine gold, Bandler is selling them the picks and shovels. Understanding NLP as sales driven explains the primary focus in NLP of persuasion and technique, and its lack of interest in an individual and personalized approach.

The empirical popularity of NLP is, ironically, the major selling point of NLP. NLP is effective at selling itself, and has successfully convinced millions of people worldwide to defend it and practice it in the face of all evidence. From this perspective, it "works" on a meta level — if you read Frogs Into Princes and focus on the storytelling techniques rather than the actual content of the book, you will come away impressed by how well they sell the story — indeed, many cult leaders have borrowed techniques from NLP training programs for indoctrination purposes. However, this "peeking behind the curtain" is not something that NLP encourages, and for all that NLP purports to reveal the mechanics of human communication, it goes to some lengths to obfuscate its own workings.

NLP appropriates and renames many techniques and approaches that did not originate from NLP, and tries to present them as an inherent part of NLP. For example, pacing and leading can be traced back to Welch and Skinner. This is an underrecognized problem, because the academic and clinical communities immediately identify and filter out misattributed sources to focus on the unique claims of NLP, while the lay public assumes that NLP is responsible for all of it. This not only further muddies the waters and separates NLP practitioners from the clinical community, but it keeps NLP perpetually behind modern clinical practices.

NLP also has a more subtle problem: it values form over substance. Bandler began learning by copying Perls down to his speech mannerisms, but he never researched the origins of Gestalt Theory. Erickson was bemused at Bandler’s take on his work, allegedly saying that "Those Bandler and Grinder boys really cracked the nut on my work… the trouble is they took the shell and left the nut." Wiezenhoffer collaborates Erickson, saying "One of the most striking features of the Bandler/Grinder interpretation is that it somehow ignores the issue of the existence and function of suggestion, which even in Erickson’s own writings and those done with Rossi, is a central idea." No matter the topic, Bandler’s inquiry is always incurious and incoherent, copying and imitating techniques without any depth or understanding, like copying the song lyrics without listening to the music.

NLP also suffers from being very much a product of its time. All of the terms and concepts used in NLP, even down to the name, are based around linguistics and psychology concepts of the 1970s, and it has not kept up with the times. Bandler has reportedly said "Everything we’re going to teach you is bullshit. But, it’s useful bullshit." I don’t think this is true: NLP is not all that useful when you can get better, more recent, and more organized information without any bullshit at all. Modern linguistics and modern neuropsychology do not map to the NLP view of language and neurological constructs. Even modern sales and marketing frameworks do not include NLP — you won’t find it in Persuasive Patterns, for example.

There’s the claim that NLP is intended to be helpful. I don’t believe this. I think NLP might have been formed with good intentions, but I think that any such intentions have fallen by the wayside as NLP went from therapy to business training. From his own words, Bandler based his core claims on hallucinations while an undergraduate, has been diagnosed as a sociopath, has made millions from NLP conferences, and had a notable cocaine habit even during the 80s. He has had every motivation to sell and make money. Bandler could have followed up on his statement that PRS was "no longer important" and rewritten his books and course materials to better reflect modern-day research and evidence. He could have encouraged people to treat NLP as an adjunct solution to other forms of treatment; instead, NLP shortchanges its practitioners by closing off other avenues of thought in favor of pure NLP. He has shown no interest in doing so. Other than enforcing rules on who can train various courses, practitioners operate independently with no required supervision, mandatory reporting, periodic competency reviews, or enforceable ethical standards beyond voluntary membership terms. Bandler’s organization shows a complete lack of care and concern about the quality of service that NLP practitioners provide.

There’s another argument that even if Bandler’s motives are suspect, many NLP trainers and practitioners do have good intent and are trying to be helpful. This is absolutely true, but the desire to be helpful does not magically endow people with the skills to actually help, and NLP’s methods does not do a good job of providing these people with the tools they need to help people. While it is unquestionably true that there are talented people that have helped people and consider themselves NLP practitioners, it is also unquestionably true that there are many more untalented people than there are talented people. NLP pushes these people through short training classes with appropriated techniques and outdated theory, does not monitor them or vet them in any way, and does not hold them to any kind of standard.

Wordweaver makes the argument that there exists a "Folk NLP" — a folk science evolution of the original. I think that even if it can be effectively distinguished and categorized, it is not relevant.

-

First, I believe that Folk NLP is not the primary strain: NLP is readily available from the unfiltered source, and per Darren Brown’s account, NLP trainers are often credentialed after four days of training with no folk immersion. Per Pseudoscience and Charlatanry in Coaching : "Rijk et al. (2019) have summarized and discussed a Delphi Poll with NLP experts, trying to identify the tools, techniques and theoretical framework which they consider to belong to NLP. The results show that there is especially high consensus that the foundation principles and techniques introduced by Bandler and Grinder are still widely used as the basis of NLP."

-

Second, if Folk NLP is a removal of the discredited core of NLP, then this leads to a Ship of Theseus problem: if all the original parts of NLP are removed to make it workable, it can hardly be called NLP any more. To quote Samuel Johnson, "Your manuscript is both good and original; but the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good."

-

Third, there is evidence that folk NLP is not a clean take — even Hypnosis Without Trance still draws from the original NLP framework despite attempting to debunk some hypnosis myths.

Again, for the purposes of recreational hypnosis, it’s okay to play with NLP. If you tell your partner "I’m using NLP on you to see your eye movements" or suggest that your partner is visually oriented and then start using visual language on them, that is a perfectly fine and valid activity. However, if you are worrying about VAKOB or trying to remember the Milton Model or Meta Model, you have my permission to relax and never think about NLP again ever.

Addendum: Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories

(This is an addendum coming from my reddit response. Apologies that it doesn’t fit into the chronology.)

Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories (RTM) comes from Frank Bourke and Richard Gray, both officers of Research and Recognition Project, a non-profit organization founded specifically to "advance the science of Neuro-Linguistic Programming." RTM has been published in peer-reviewed journals — there are five studies I can find — and the effect results are pretty extraordinary, with one study showing a 1.45 - 3.7 range.

There are several problems with the studies though. In a meta analysis, the reviewers rated RTM studies as having "high risk of bias" with a GRADE rating of "very low" (the lowest possible evidence quality designation). The studies have methodological issues: the sample sizes are small, they used waitlist controls rather than active treatment comparisons, the populations are narrow, they used non-random sampling, and the follow up periods are short.

All of this is from a single research team with a direct interest in the protocol’s success. Four out of the five studies came from Bourke and Grey, and the fifth was an efficiency study. There are no independent replications outside of Bourke and Grey.

The extraordinary effect sizes (2-3x larger than established treatments) would revolutionize PTSD treatments, and the VA should have been crawling over itself to try to reproduce this. Despite that… it’s been over 10 years and it’s not in their clinical practice guidelines, it’s not in the APAs guidelines, it is in ISTSS but as an intervention with emerging evidence which is explicitly listing experimental treatments. There is a clinical trial but it was registered in 2019 and is still unpublished over six years later — if the results were strongly positive, you’d expect publication. There is a case study but this is the lowest tier of evidence from an open access journal with minimal peer review.

This isn’t to say that RTM doesn’t work — it’s technically possible that it might be everything it claims to be. But even in the most generous ISTSS case, it’s something to try when more proven methods have been tried and didn’t work, i.e. CPT, PE, EMDR etc. There just isn’t enough evidence to show that it’s something to lead with.